Jataka 178

Kacchapa Jātaka

The Tortoise

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by William Henry Denham Rouse, Cambridge University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

This is a story with some not-so-subtle Buddhist themes. First and foremost, it is a story about being practical. While of course Buddhism is a mystical tradition, it is also compellingly practical. But this story is also about Buddhism’s old friends: craving, clinging, and attachment.

“Here was I born.” The Master told this story while he was Jetavana. It is about how a man overcame malaria.

Malaria once broke out in a family from Sāvatthi. The parents said to their son, “Don’t stay in this house, son. Make a hole in the wall and escape somewhere and save your life. (The belief was that malaria was caused by a spirit who would guard the door. The hole in the wall was a way to escape from it.) Then come back again. There is a great hoard of treasure buried here. Dig it up, restore the family fortunes, and have a happy life.”

The young fellow did as he was told. He broke through the wall and made his escape. When the disease had run its course, he returned and dug the treasure up, and he used it to establish his household.

One day, laden with oil and ghee, clothes and other offerings, he went to Jetavana. There he greeted the Master and took his seat. The Master entered into a conversation with him. “We hear,” he said, “that you had disease in your house. How did you escape it?” He told the Master all about it. The Master said, “In days gone by, as now, friend layman, when danger arose, there were people who were too fond of home to leave it. As a result they perished, while those who were not afraid to leave went elsewhere and saved themselves.” And then at his request the Master told this story from the past.

Once upon a time, when Brahmadatta was reigning in Benares, the Bodhisatta was born in a village as a potter’s son. He worked at the potter’s trade, and he had a wife and family to support.

At that time there lay a great natural lake close to the great river of Benares. When there was a lot of water, the river and lake merged into one body of water, but when the water was low, they were distinct.

Now fish and tortoises know by their instincts when the year will be rainy and when there will be a drought. So at the time of our story the fish and the tortoises that lived in that lake knew there would be a drought. So when the river and the lake were one water, they swam out of the lake into the river. But there was one tortoise who would not go into the river because, he said, “I was born here, and here I have grown up. Here is my parents’ home. I cannot leave it!”

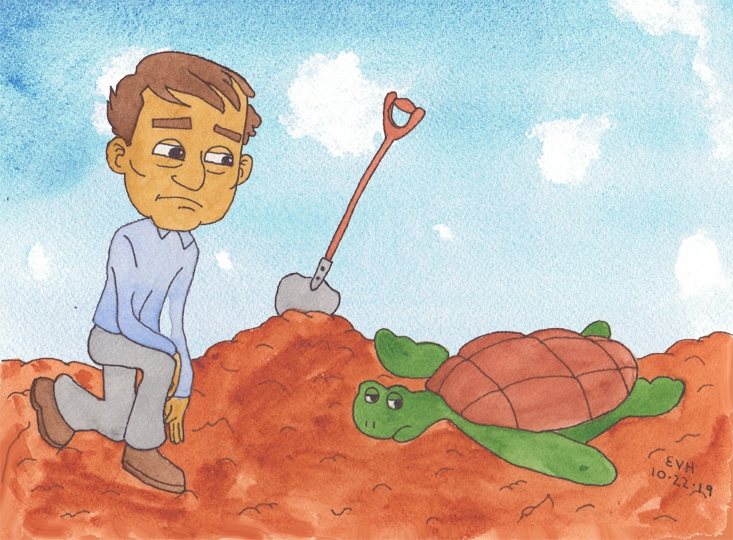

When the hot season came all of the water dried up. He dug a hole and buried himself, right in the place where the Bodhisatta got his clay. One day when the Bodhisatta went to get some clay, he dug down with a big shovel until he cracked the tortoise’s shell. He turned him over on the ground as though he were a large piece of clay. In his agony the creature thought, “Here I am, dying, all because I was too attached to my home to leave it!” and in the words of these verses he bemoaned:

“Here was I born, and here I lived. My refuge was the clay.

And now the clay has played me false in a most grievous way.

You, you I call, O potter. Now hear what I have to say!

“Go where you can find happiness, wherever the place may be,

Forest or village, there the wise both home and birthplace see.

Go where there’s life. Don’t stay at home for death to master thee.”

Figure: Too Attached, and Now, Too Dead

So he went on and on, talking to the Bodhisatta until he died. The Bodhisatta picked him up. He gathered all the villagers together and addressed them, “Look at this tortoise. When the other fish and tortoises went into the great river, he was too attached to his home to go with them. He buried himself in the place where I get my clay. Then as I was digging for clay, I broke his shell with my big shovel, and turned him out on the ground believing that he was a large lump of clay. He told me what he had done, lamenting his fate in two verses of poetry. Then he died. So you see he came to his end because he was too attached to his home. Take care not to be like this tortoise. Don’t say to yourselves, ‘I have sight, I have hearing, I have smell, I have taste, I have touch, I have a son, I have a daughter, I have numbers of men and maids for my service, I have precious gold.’ Do not cling to these things with craving and desire. Each being passes through three stages of existence” (birth, death, rebirth).

In this way he exhorted the crowd with the skill of a Buddha. The discourse was spread all over India, and it was remembered for 7,000 years. The whole village lived in accordance with his teaching. They gave alms and did good deeds until they were reborn in the heavenly realms.

When the Master finished telling this story, he taught the Four Noble Truths. At the conclusion of the teaching the young man was established in the Fruit of the First Path (stream-entry). Then the Master identified the birth: “Ānanda was the tortoise, and I was the potter.”