Jataka 179

Satadhamma Jātaka

The Story of Satadhamma

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by William Henry Denham Rouse, Cambridge University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

This is a very curious story. It feels like it came from a later time when Brahminism (early Hinduism) and Buddhism has started to merge together. This happened especially in Vajrayana Buddhism (Tibetan Buddhism), which fused together elements of Brahminism, Buddhism, and animism. The story defends the practice of high caste people not accepting anything from a low cast person, which is most definitely not a teaching of the Buddha. The Buddha’s Saṇgha was open to all people (including women!), and all were treated as equals.

Despite this religious fusion, the purpose of this story may be to inform lay people about some of the violations of the monastic code. One of the responsibilities of lay people is to ensure that the monastics are behaving properly. If the monastics misbehave, the lay people have recourse by withholding the requisites. It’s a system of checks and balances.

It is also strange that the Bodhisatta is from the low caste, but is not given any respect.

“What a trifle.” The Master told this story while he was at Jetavana. It is about the 21 unlawful ways of acquiring the requisites.

At one time there were a great many monks who used to earn a living as physicians, or runners (doing errands on foot), exchanging alms for alms (storing food overnight), and so on, the 21 unlawful callings. All this will be set forth in the Sāketa Birth (Jātaka 238. However Jātaka 238 simply refers to Jātaka 68). When the Master found out what they were doing, he said, “Now there are a great many monks who are violating the monastic code. Those who do these things will not escape birth as goblins or disembodied spirits. They will become beasts of burden. They will be born in hell. For their benefit and blessing it is necessary to give a discourse that makes its meaning clear and plain.”

So he gathered the Saṇgha together, and said, “Monks, you must not acquire the requisites (food, clothing, shelter, and medicine) by the 21 unlawful methods. Food won unlawfully is like a piece of red-hot iron, like a deadly poison. These unlawful actions are blamed and rebuked by disciples of all Buddhas and Pacceka-Buddhas (“Solitary” or non-teaching Buddha). For those who eat food gained by unlawful means there is no laughter and no joy. Food obtained in this way, in my teaching, is like the garbage of the lowest caste. To take it, for a disciple of the true Dharma, is like taking the waste of the vilest of mankind.” And with these words, he told this story from the past.

Once upon a time, when Brahmadatta was the King of Benares, the Bodhisatta was born as the son of a man of the lowest caste. When he grew up, he left his home on a journey, taking some rice grains in a basket for his food.

At that time there was a young fellow in Benares. His name was Satadhamma. He was the son of a powerful person, a northern brahmin. He also left on a journey, but he did not take rice grains or even a basket. The two met on the highway. The young brahmin said to the other, “What caste are you from?”

He replied, “Of the lowest. And what caste are you from?”

”Oh, I am a northern brahmin.”

“All right, let us travel together.” And so they did.

When breakfast time came, the Bodhisatta sat down where there was some nice water. He washed his hands and opened his basket. “Will you have some?” he said.

“Tut, tut,” Satadhamma said. “I don’t want any of your low caste food.”

“All right,” the Bodhisatta said.

Careful to waste nothing, he put as much as he wanted in a leaf, fastened up his basket, and ate. Then he took a drink of water, washed his hands and feet, and picked up the rest of his rice and food. “Come along, young sir,” he said, and they started off again on their journey.

All day they tramped along, and in the evening they both had a bath in some nice water. When they came out, the Bodhisatta sat down in a nice place, undid his parcel, and began to eat. This time he did not offer any food to Satadhamma. The young gentleman was tired from walking all day. He was hungry to the bottom of his soul. He stood there looking on and thinking, “If he offers me anything, I’ll take it.” But the Bodhisatta ate away without a word.

“This low fellow,” Satadhamma thought, “eats every scrap without a word. Well, I’ll ask for a piece. I can throw away the outside, which is defiled and eat the rest.”

And so he did. He ate what was left. But as soon as he had eaten, he thought, “How I have disgraced my birth, my clan, my family! Why, I have eaten the leavings of a low born peasant!”

He felt so disgraced that he threw up the food, and blood came with it. “Oh, what a wicked thing I have done,” he cried, “all for the sake of a trifle!” And he said these words of the first stanza:

“What a trifle! and his leavings! given too against his will!

And I am a highborn brahmin, and the stuff has made me ill!”

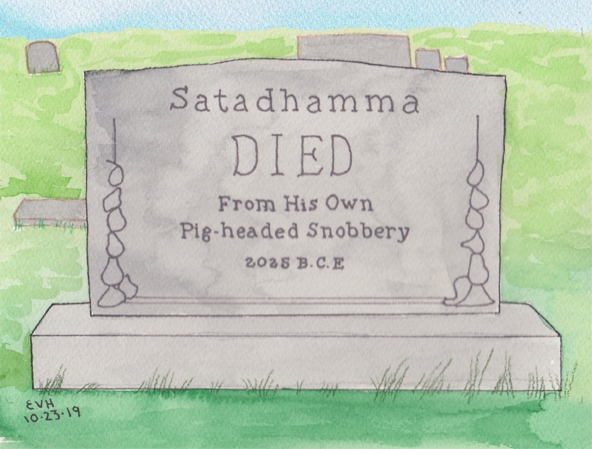

Thus did the young gentleman lament, adding, “Why did I do such a wicked thing just for life's sake?” He plunged into the jungle, and never let anyone see him again. There he died forlorn.

Figure: He Died Forlorn

When this story ended, the Master repeated, “Just as the young brahmin, monks, after eating the leavings of a low-caste man, found that neither laughter nor joy was for him because he had taken improper food. So whoever seeks liberation and gains the requisites by unlawful means, when he eats the food and supports his life in any way that is blameworthy and disapproved by the Buddha, will find that there is no laughter and no joy for him.” Then, becoming perfectly serene, he repeated the second stanza:

“He that lives by being wicked, he that cares not if he errs,

Like the brahmin in the story, has no joy with his affairs.”

When this discourse was concluded, the Master taught the Four Noble Truths, at the conclusion of which many monks attained stream-entry. Then the Buddha identified the birth, saying, “At the time of the story I was the low-caste man.”