Jataka 314

Lohakumbhi Jātaka

The Iron Cauldron

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by H.T. Francis and R.A. Neil, Cambridge University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

To a Westerner who has rejected the dogmatic side of Christianity, stories like this may not sit well. But in Buddhism, it is not a deity that determines our future; it is our karma. It is the fruits—good or bad—of our actions that determines our future. But the Canon is clear that for someone who commits misdeeds, the consequences can be extremely grave.

The good news is that a) we have control over our futures by cultivating good qualities, and b) that even if we have an unpleasant rebirth, eventually we will have a better one. And that will be a time when—hopefully—we will have learned from our past mistakes, and we can be more skillful, kind beings.

“Due share of wealth.” The Master told this story while he was living at Jetavana. It is about a King of Kosala. The King of Kosala of those days, they say, heard a cry one night that was uttered by four inhabitants of Hell. He heard the syllables “du,” “sa,” “na,” and “soo,” one from each of the four. In a previous existence, tradition says, they had been princes in Sāvatthi, and they had been guilty of adultery. After the misconduct with their neighbors’ wives, no matter how carefully they hid their misdeeds, their evil lives were cut short by the Wheel of Death near Sāvatthi.

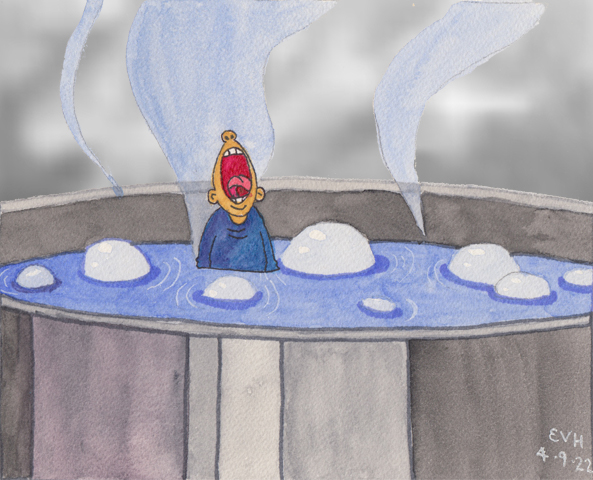

They were reborn in four iron cauldrons. After being tortured for 60,000 years, they had bubbled up to the top. And on seeing the edge of the cauldron’s mouth they thought to themselves, “When shall we escape from this misery?” And then all four uttered a loud cry, one after another. The King was terrified to death at the noise, and he sat waiting for the break of day, unable to stir.

At dawn the brahmins came and inquired after his health. The King replied, “How, my Masters, can I be well, when today I heard four terrible cries.” The brahmins waved their hands. “What is it, my Masters?” said the King. The brahmins told him that the sounds were omens of great violence. “Is there a remedy, or not?” said the King. “You might say not,” said the brahmins, “but we are well-trained in these matters, sire.” “By what means,” said the King, "will you avert these evils?” “Sire,” they replied, “there is one great remedy in our power. By offering the fourfold sacrifice of every living creature, we will avert all evil.” “Then be quick,” said the King, “and take all living creatures by fours—men, bulls, horses, elephants, down to quails and other birds—and by this fourfold sacrifice restore my peace of mind.”

The brahmins consented, and taking whatever they required, they dug a sacrificial pit and fastened the victims to their stakes. They were highly excited at the thought of the delicacies they were to eat and the wealth they would gain. (They could basically ask any price for their services.) And so they went about backwards and forwards, saying, “Sir, I must have this and that.”

The Queen Mallikā came and asked the King why the brahmins were so delighted and smiling. The King said, “My Queen, what do you have to do with this? You are intoxicated with your own glory, and you do not know how wretched I am.” “How so, sire?” she replied. “I have heard such awful noises, my Queen, and when I asked the brahmins what would be the result of my hearing these cries, they told me I was threatened with danger to my kingdom or my property or my life. But by offering the fourfold sacrifice they would restore my peace of mind. And now in obedience to my command, they have dug a sacrificial pit and have gone to fetch whatever victims they require.” The Queen said, “Have you, my lord, consulted the chief brahmin in the Deva world as to the origin of these cries?” “Who, lady,” said the King, “is the chief brahmin in the Deva world?” “The Great Gotama,” she replied, “the Supreme Buddha.” “Lady,” he said, “I have not consulted the Supreme Buddha.” “Then go,” she answered, “and consult him.”

The King heeded the words of the Queen, and after his morning meal, he mounted his state chariot and drove to Jetavana. Here—after saluting the Master—he addressed him: “Reverend sir, in the night I heard four cries and consulted the brahmins about it. They undertook to restore my peace of mind by the fourfold sacrifice of every kind of victim, and now they are busy preparing a sacrificial pit. What does the hearing of these cries mean for me?”

“Nothing whatever,” said the Master. “Certain beings in Hell, because of the agony they suffer, cried aloud. These cries,” he added, “have not been heard by you alone. Kings of old heard them just the same. And they, too, after consulting their brahmins, were anxious to offer sacrifices of slain victims. But on hearing what wise men had to say, they refused to do so. The wise men explained to them the nature of these cries, and told them to release the crowd of victims. And in this way they restored their peace of mind.” And at the request of the King, he told him this story from the past.

Once upon a time when Brahmadatta was reigning in Benares, the Bodhisatta was reborn into a brahmin family in a certain village of Kāsi. And when he was of mature years, he renounced sensual pleasures and embraced the holy life. He developed the supernatural powers of deep meditation and enjoyed the delights of the contemplative life. He did this while living in a pleasant grove in the Himālaya country.

The King of Benares at this time was greatly alarmed by hearing those four sounds uttered by the four beings who lived in Hell. And when he was told by brahmins in exactly the same way that one of three dangers must befall him, he agreed to their proposal to put a stop to it by the fourfold sacrifice. The family priest—with the help of the brahmins—provided a sacrificial pit. And a great crowd of victims was brought up and fastened to the stakes.

Then the Bodhisatta, guided by a feeling of compassion, observed the world with his divine eye. When he saw what was going on, he said, “I must go at once and see to the well-being of all these creatures.” And then—by his magic power—he flew up into the air. He landed in the garden of the King of Benares. He sat down on the royal slab of stone, looking like an image of gold. The chief disciple of the family priest approached his teacher and asked, “Is it not written, Master, in our Vedas that there is no happiness for those who take the life of any creature?” The priest replied, “You are to bring the King’s property here, and we will have abundant dainties to eat. Only hold your tongue.” And with these words he drove his pupil away.

But the youth thought, “I will have no part in this matter.” He went and found the Bodhisatta in the King’s garden. After greeting him in a friendly manner, he took a seat at a respectful distance. The Bodhisatta asked him, “Young man, does the King rule his kingdom righteously?” "Yes, Reverend Sir, he does,” answered the youth, “but he heard four cries in the night. When he asked the brahmins about this, they told him that they would restore his peace of mind by offering up the fourfold sacrifice. So the King, being anxious to recover his happiness, is preparing a sacrifice of animals. A great number of victims has been brought up and fastened to the sacrificial stakes. Now is it not right for holy men like yourself to explain the cause of these noises and to rescue these numerous victims from the jaws of death?”

“Young man,” he replied, “the King does not know me, and I do not know the King. But we do know the origin of these cries, and if the King would come and ask me the cause, I would resolve his doubts for him.”

“Then,” said the youth, “just stay here a moment, Reverend Sir, and I will bring the King to you.”

The Bodhisatta agreed. The youth went and told the King all about his conversation, and he brought the King back with him. The King saluted the Bodhisatta, and sitting on one side, he asked him if it were true that he knew the origin of these noises. “Yes, Your Majesty,” he said. “Then tell me, Reverend Sir.” “Sire,” he answered, “these men in a former existence were guilty of gross misconduct with the carefully guarded wives of their neighbors near Benares. Therefore they were re-born in four iron cauldrons. There—after being tortured for 30,000 years in a thick corrosive liquid heated to boiling point—they would at one time sink until they struck the bottom of the cauldron. At another time they would rise to the top like a foam bubble. But after all those years they found the mouth of the cauldron, and looking over the edge they all four desired to cry out four complete stanzas. But they failed to do so. And after getting out just one syllable each, they sank again into the iron cauldrons. Now the one of them that sank after uttering the syllable “du” was anxious to speak as follows:

Due share of wealth we gave not, an evil life we led,

We found no sure salvation in joys that now are fled.

And when he failed to utter it, the Bodhisatta of his own knowledge repeated the complete stanza. And similarly with the rest. The one that uttered merely the syllable “sa” wanted to repeat the following stanza:

Sad fate of those that suffer! Ah! When shall come release?

Still after countless eons, Hell’s tortures never cease.

And again in the case of the one that uttered the syllable “na,” this was the stanza he wished to repeat:

Nay endless are the sufferings to which we’re doomed by fate,

The ills we wrought upon the earth we cannot subjugate.

And the one that uttered the syllable “soo” was anxious to repeat the following:

Soon shall I passing forth from here, attain to human birth,

And richly dowered with virtue rise to many a deed of worth.

The Bodhisatta, after reciting these verses one by one, said, “The dweller in Hell, sire, when he wanted to utter a complete stanza, because of the greatness of his misdeed, was unable to do it. And when he then experienced the result of his wrong-doing, he cried aloud. But fear not. No danger will come to you just because you heard this cry.”

Figure: “He cried aloud…”

In this way he reassured the King. And the King proclaimed by beat of his golden drum that the vast host of victims was to be released and the sacrificial pit destroyed. And the Bodhisatta, after providing for the safety of the numerous victims, stayed there a few days. Then he returned back to the place from which he had come. And without any break in his meditative bliss, he was reborn in the world of Brahma.

The Master, having ended his lesson, identified the birth: “At that time Sāriputta was the young priest, and I was the recluse.”