Jataka 316

Sasa Jātaka

The Rabbit

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by H.T. Francis and R.A. Neil, Cambridge University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

This is another story about generosity. It brings to mind this famous discourse of the Buddha:

“

This was said by the Lord…

“Bhikkhus, if beings knew, as I know, the result of giving and sharing, they would not eat without having given, nor would they allow the stain of meanness to obsess them and take root in their minds. Even if it were their last morsel, their last mouthful, they would not eat without having shared it, if there were someone to share it with. But, bhikkhus, as beings do not know, as I know, the result of giving and sharing, they eat without having given, and the stain of meanness obsesses them and takes root in their minds.”

If beings only knew—

So said the Great Sage—

How the result of sharing

Is of such great fruit,

With a gladdened mind,

Rid of the stain of meanness,

They would duly give to noble ones

Who make what is given fruitful.

Having given much food as offerings

To those most worthy of offerings,

The donors go to heaven

On departing the human state.

Having gone to heaven they rejoice,

And enjoying pleasures there,

The unselfish experience the result

Of generously sharing with others.

— [Iti 26]

“

“Seven red fish.” The Master told this story while living at Jetavana. It is about a gift of all the Buddhist requisites (food, clothing, shelter, medicine). A certain landowner at Sāvatthi, they say, provided all the requisites for the Saṇgha with the Buddha at its head. He set up a pavilion at his house door and invited all the monks with their chief, the Buddha. He seated them on elegant seats prepared for them and offered them a variety of choice and fine food. And saying, “Come again tomorrow,” he entertained them for a whole week. On the seventh day he presented Buddha and the 500 monks under him with all the requisites. At the end of the feast the Master, in returning thanks, said, “Lay brother, you are right in giving pleasure and satisfaction by this charity. For this is a tradition of wise men of old who sacrificed their lives for any recluses with whom they met. He even gave them their own flesh to eat.” And at the request of his host he told this story from the past.

Once upon a time when Brahmadatta was reigning in Benares, the Bodhisatta was reborn as a young hare. He lived in a wood. On one side of this wood was the foot of a mountain, on another side a river, and on the third side a border village. The hare had three friends: a monkey, a jackal, and an otter. These four wise creatures lived together, and each of them got his food in his own hunting ground. In the evening they came back together again. The hare—in his wisdom—taught the Dharma to his three companions. He taught that alms are to be given, the moral law is to be observed, and holy days are to be kept. They accepted his teaching, and each of them went to his own part of the jungle and lived there.

And so in the course of time, one day the Bodhisatta looked up at the sky. Seeing the moon, he knew that the next day would be a holy day (Uposatha). He addressed his three companions and said, “Tomorrow is a holy day. Let all three of you follow the moral precepts and observe the holy day. To one that stands firm in moral practice, giving alms brings a great reward. Therefore feed any beggars that come to you by giving them food from your own table.” They readily agreed, and each of them went off to his own place of living.

On the next day, quite early in the morning, the otter went out to seek his prey. He went down to the bank of the Ganges. Now it came to pass that a fisherman had caught seven red fish. He strung them together on a willow branch. He had taken and buried them in the sand on the river’s bank. And then he went back down to the stream in order to catch more fish. The otter smelled the buried fish. He dug up the sand until he found them. And pulling them out he cried aloud three times, "Does anyone own these fish?” (Saying it three times made it ”legal,” i.e., it was not stealing.) And not seeing any owner, he took hold of the willow branch with his teeth and took the fish into the jungle where he lived, intending to eat them at a fitting time. And then he lay down, thinking how virtuous he was.

The jackal, too, went forth in search of food. In the hut of a field watcher he found two spits. One had a lizard, and one had a pot of milk curd. And after crying aloud three times, “To whom do these belong?” and not finding an owner, he put the rope for lifting the pot around his neck. And grasping the spits and the lizard with his teeth, he took them into his own lair, thinking, “In due time I will eat them.” Then he lay down, reflecting on how virtuous he had been.

The monkey also entered a clump of trees. And gathering a bunch of mangoes, he took them into his part of the jungle. He intended to eat them in due time. Then he lay down, thinking how virtuous he was.

But the Bodhisatta in due time came out intending to graze on the kuça grass. And as he lay in the jungle, the thought occurred to him, “It is impossible for me to offer grass to any beggars that may appear by chance. And I have no oil or rice and anything like that. If any beggar appeals to me, I will have to give him my own flesh to eat.”

At this splendid display of virtue, Sakka’s white marble throne heated up. (This happened anytime something auspicious happened.) Sakka, on reflection, discovered the cause. He resolved to test this noble hare. First he went and stood by the otter’s living place disguised as a brahmin. The otter asked him why he stood there. He replied, “Wise sir, if I could get something to eat, after keeping the fast, I would perform all my priestly duties.” The otter replied, “Very well, I will give you some food,” and as he talked with him he repeated the first stanza:

Seven red fish I safely brought to land from Ganges flood,

O brahmin, eat your fill, I pray, and stay within this wood.

The brahmin said, “Let it wait until tomorrow. I will see to it by and bye.”

Next he went to the jackal. The jackal asked him why he stood there. He gave the same reply. The jackal, too, readily promised him some food, and in talking with him he repeated the second stanza:

A lizard and a jar of curds, the keeper’s evening meal,

Two spits to roast the flesh withal I wrongfully did steal.

Such as I have I give to you, O brahmin, eat, I pray,

If you should decide within this wood a while with us to stay.

Said the brahmin, “Let it wait until tomorrow. I will see to it by and bye.”

Then he went to the monkey, and when asked what he was doing standing there, he answered just as before. The monkey readily offered him some food, and in talking with him uttered the third stanza:

An icy stream, a mango ripe, and pleasant greenwood shade,

’Tis yours to enjoy, if you can live content in forest glade.

The brahmin said, “Let it wait until tomorrow. I will see to it by and bye.”

And then he went to the wise hare. When he was asked why he stood there, he made the same reply. The Bodhisatta—on hearing what he wanted—was highly delighted. He said, “Brahmin, you have done well in coming to me for food. On this day I will grant you a boon that I have never granted before. However, you will not break the moral law by taking animal life. Go, friend, and when you have piled together logs of wood and kindled a fire, come and let me know. I will sacrifice myself by falling into the midst of the flames. And when my body is roasted, you will eat my flesh and fulfill all your priestly duties.” And in addressing him in this way the hare uttered the fourth stanza:

Nor sesame, nor beans, nor rice have I as food to give,

But roast with fire my flesh I yield, if you with us would live.

Sakka, on hearing what he said, by his miraculous power caused a heap of burning coals to appear. Rising from his bed of kuça grass, the Bodhisatta shook himself three times in case there were any insects in his fir, so they might escape death. Then offering his whole body as a free gift, he leaped up. And like a royal swan, he landed on a cluster of lotuses. Then, in an elation of joy, he fell on the heap of live coals.

But the flame failed to so much as warm the pores of the hair on the body of the Bodhisatta. It was as if he had entered a region of frost. Then he addressed Sakka in these words: “Brahmin, the fire you have kindled is icy cold. It fails to even warm the pores of the hair on my body. What is the meaning of this?”

Figure: “What is the meaning of this?”

“Wise sir,” he replied, “I am no brahmin. I am Sakka, and I have come to test your virtue.”

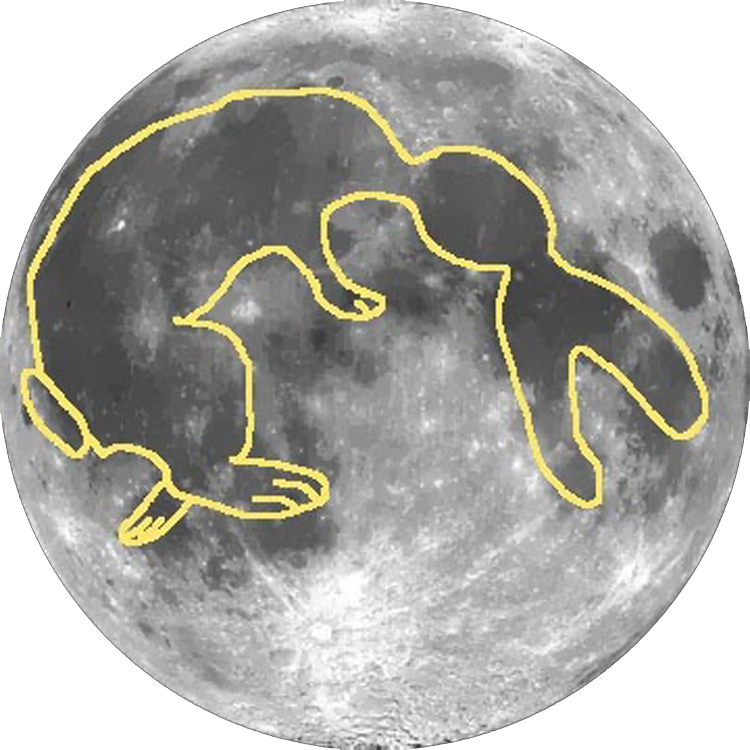

The Bodhisatta said, “If not only you, Sakka, but all the inhabitants of the world were to test me in this matter of almsgiving, they would not find in me any unwillingness to give.” And with this the Bodhisatta uttered a cry of exultation like a lion roaring. Then Sakka said to the Bodhisatta, “O wise hare, let your virtue be known throughout the whole world.” And squeezing the mountain, he extracted its essence. He daubed the sign of a hare on the face of the moon. (In Eastern lore there is a “moon rabbit,” i.e., the image of a rabbit on the face of the moon.) And after depositing the hare on a bed of young kuça grass in the same wooded part of the jungle, Sakka returned to his own place in heaven. And these four wise creatures lived happily and harmoniously together. They observed the moral law and the holy days until they departed to fare according to their karma.

The Master, when he had ended his lesson, taught the Four Noble Truths. And at the conclusion of the teaching, the householder who gave as a free gift all the Buddhist requisites, attained steam-entry. Then the Master identified the birth: “At that time Ānanda was the otter, Moggallāna was the jackal, Sāriputta was the monkey, and I was the wise hare.”

Figure: The Moon Rabbit