Jataka 317

Matarodana Jātaka

The Story of Matarodana

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by H.T. Francis and R.A. Neil, Cambridge University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

The inevitability of death is a common theme in the Buddha’s teaching. Yet I am constantly surprised—even astonished—that even though we all know that everyone will die, some people are so shocked when it happens. But in the Dharma death is simply a part of the cycle of life. It is not a cause for grief. If someone has led a good life and developed good qualities, they will have a good rebirth. What is a cause for grief is when someone dies having wasted their entire life doing meaningless things.

“Weep for the living.” The Master told this story while in residence at Jetavana. It is about a certain landowner who lived at Sāvatthi.

On the death of his brother, it is said, he was so overwhelmed with grief that he neither ate nor washed nor cared for himself. Every morning he went to the cemetery at daybreak in deep misery to weep. Early one morning, the Master cast his eye upon the world and saw a capacity for attaining to the fruition of the First Path (stream-entry) in that man. He said, “There is no one but myself who can relieve his grief and bring him to the fruition of the First Path by telling him what happened long ago. I must be his refuge.”

So on the next afternoon after returning from his alms round, he took a junior monk and went to his house. On hearing of the Master’s arrival, the landowner ordered a seat to be prepared. He invited him to enter, and—saluting him—he sat on one side. The Master asked him why he was grieving. He answered that he had been sorrowing ever since his brother’s death. The Master said, “All compound existences are impermanent, and what is to be broken is broken. One should not trouble about this. Wise men of old, from knowing this, did not grieve when their brother died.” And at his request the Master told him this story from the past.

Once upon a time when Brahmadatta was reigning in Benares, the Bodhisatta was reborn into the family of a rich merchant. This family was worth eighty crores (1 crore equals 10 million rupees.). When he came of age, his parents died. On their death the Bodhisatta’s brother managed the family estate, and the Bodhisatta lived in dependence on him. By and bye the brother also died of a fatal disease. His relations, friends, and companions gathered together. They threw up their arms, wept and lamented, and no one was able to control his feelings. But the Bodhisatta neither lamented nor wept. People said, “See now, though his brother is dead, he does not so much as show a sad face. He is a very hard-hearted fellow. I think he wanted his brother to die, hoping to enjoy all of his family’s wealth.”

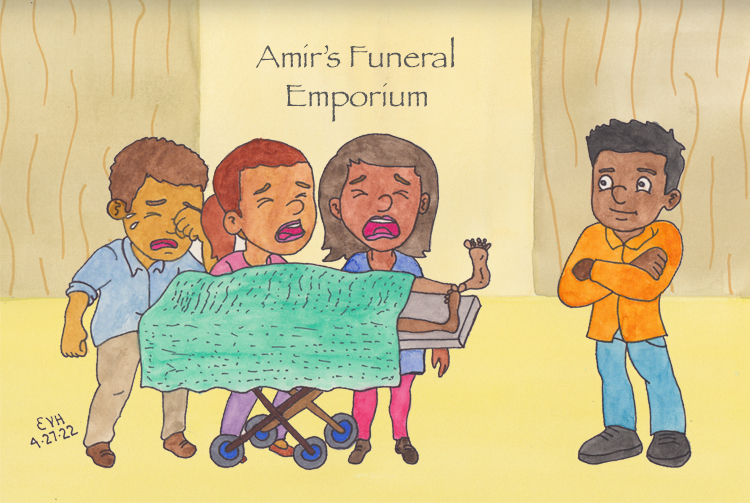

Figure: “In your blind folly… you weep and cry.”

In this way they criticized the Bodhisatta. His family also rebuked him, saying, “Even though your brother is dead, you do not shed a tear.” On hearing their words he said, “In your blind folly, not knowing the Eight Worldly Conditions (gain and loss, pleasure and pain, praise and blame, and fame and disgrace), you weep and cry, ‘Alas! My brother is dead.’ But I, too—and you also—will have to die. Why then do you not weep at the thought of your own death? All existing things are impermanent, and consequently no single compound is able to remain in its natural condition. Though you, blind fools, in your state of ignorance, from not knowing the Eight Worldly Conditions, weep and lament. Why should I weep?” And so saying, he repeated these stanzas:

Weep for the living rather than the dead!

All creatures that a mortal form do take,

Four-footed beast and bird and hooded snake,

Yea men and devas all the same path tread.

Powerless to cope with fate, rejoiced to die,

Amid sad alternation of bliss and pain,

Why shedding idle tears should any complain,

And plunged in sorrow for a brother sigh?

Those versed in fraud and in excess grown old,

The untutored fool, even those valiant of might,

If worldly-wise and ignorant of right,

Wisdom itself as foolishness may hold.

In this way the Bodhisatta taught these people the Dharma and delivered them all from their sorrow.

The Master, after he had ended his holy discourse, taught the Dharma, at the conclusion of which the landowner attained to the fruition of the First Path. Then the Master identified the birth: “I was the wise man who delivered people from their sorrow by his holy discourse.”