Jataka 318

Kaṇavera Jātaka

The Kaṇavera Flowers

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by H.T. Francis and R.A. Neil, Cambridge University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

This story has a familiar theme, and that is how lust can lead to one’s demise. But it is even more interesting that in this tale the Bodhisatta is a robber. In these stories the Buddha is often less than perfect (!) in his previous lives. This is the fate of everyone who is caught in the relentless grasp of saṃsara, even the Buddha to be. The only way out is to attain a full awakening, to become an arahant.

“It was a joyous time.” The Master told this story when he was at Jetavana. It is about a monk who was tempted by thoughts of the wife he had left behind. The circumstances that led up to the story will be set forth in the Indriya Birth (Jātaka 423). The Master, addressing this monk, said, “Once before, because of her, you had your head cut off.” And then he told this story from the past.

Once upon a time when Brahmadatta was reigning in Benares, the Bodhisatta was born in a village of Kāsi in the home of a certain householder. This householder was a robber. When the Bodhisatta came of age, he gained his living by robbery. His fame was blazed abroad in the world as a bold fellow who was as strong as an elephant, and no one could catch him.

One day he broke into a rich merchant’s house and carried off a great deal of treasure. The townsfolk went to the King and said, “Sire, a mighty robber is plundering the city. Have him arrested.” The King ordered the governor of the city to seize him. So during the night the governor posted men here and there in detachments. He was able to effect his capture with the money on him. The governor reported this to the King.

The King ordered the governor to cut off his head. The governor had his arms tightly bound behind him, and—having tied a wreath of red kaṇavera flowers around his neck and sprinkled brick dust on his head—he had him beaten with whips in every square. He was then led to the place of execution to the music of a harsh-sounding drum. Men said, “This predatory robber who loots our city is taken,” and the whole city was greatly moved.

At this time there was a courtesan named Sāmā who lived in Benares. Her price was a 1,000 gold coins. She was a favorite of the King’s, and he had a suite of 500 female slaves. And as she stood at an open window on the upper floor of the palace, she saw this robber being led along. Now he was handsome and gracious to look at. He stood out above all men, exceedingly glorious and god-like in appearance. And when she saw him being led past, she fell in love with him. She thought to herself, “How can I secure this man for my husband?” “This is the way,” she said. She sent one of her female attendants with 1,000 gold coins to the governor. “Tell him,” she said, “that this robber is Sāmā’s brother, and that he has no other refuge Sāmā. Ask him to accept the money and let his prisoner go free.”

The handmaid did as she was told. But the governor said, “This is a notorious robber. I cannot let him go free after what he has done. But if I could find another man as a substitute, I could put the robber in a covered carriage and send him to you.” The slave went and reported this to her mistress.

Now at this time a certain rich young merchant who was enamored of Sāmā presented her with 1,000 gold coins every day. And on that very day at sunset her lover came as usual to her house with the money. Sāmā took the money and placed it in her lap and sat weeping. When he asked what was the cause of her sorrow, she said, “My lord, this robber is my brother. But he never came to see me because people say I follow a vile trade. And when I sent a message to the governor, he said that if he were to send him 1,000 gold coins, he would let his prisoner go free. But now I cannot find anyone to go and take this money to the governor.” Because of his love for Sāmā, the youth said, “I will go.” “Go, then,” she said, “and take with you the money you brought me.” So he took it and went to the house of the governor.

The governor hid the young merchant in a secret place and had the robber conveyed in a closed carriage to Sāmā. Then he thought, “This robber is well known in the country. It must be quite dark first. And then, when all men have retired to sleep, I will have the man executed.” And so, making some excuse for delaying the execution a while, after people had retired to sleep, he sent the young merchant with a large escort to the place of execution. He had his head cut off, and then he returned into the city.

Afterwards Sāmā refused the attention of any other man. She passed all her time taking her pleasure with this robber only. The thought occurred to the robber, “If this woman falls in love with anyone else, she will have me, too, put to death and take her pleasure with him. She is very treacherous to her friends. I must not stay here any longer, and I must escape as quickly as possible.”

When he was preparing to leave, he thought, “I will not go empty-handed. I will take some of the ornaments belonging to her.” So one day he said to her, “My dear, we always stay indoors like tame cockatoos in a cage. Some day we should enjoy ourselves in the garden.” She readily agreed and prepared every kind of food, hard and soft, and decked herself out with all her ornaments. She drove to the garden with him seated in a closed carriage. While he was enjoying himself with her, he thought, “Now must be the time for me to escape.” So under a show of violent affection for her, he entered into a thicket of kaṇavera bushes, and pretending to embrace her, he squeezed her until she became unconscious. Then throwing her down, he took all her ornaments. He fastened them in her outer garment, and placing the bundle on his shoulder, he leapt over the garden wall and made off.

When she had recovered consciousness, she rose up and went and asked her attendants what had become of her young lord. “We do not know, lady.” “He thinks,” she said, “I am dead, and he must have run away in alarm.” And being distressed at the thought, she returned to her house and said, “I will not rest on a sumptuous couch until I have set eyes on my dear lord,” and she lay down on the ground. And from that day on she neither put on pretty clothes or ate more than one meal or used perfumes and ornaments and the like.

She resolved to find her lover by every possible means. She sent for some actors and gave them each 1,000 gold coins. They asked her, “What are we to do for this, lady?” She said, “There is no place that you do not visit. Go to every village, town and city. Gather a crowd around you. First of all, sing this song in the midst of the people.” Then she taught them the first stanza of a song. “And if,” she said, “when you have sung this song, if my husband is in the crowd, he will speak to you. Then you may tell him I am quite well and bring him back with you. If he refuses to come, send me a message.”

And giving them their expenses for the journey, she sent them off. They started from Benares. Calling the people together here and there, they arrived at last at a border village. Now the robber, since his flight, had been living here. The actors gathered a crowd about them, and sang the first stanza:

’Twas the joyous time of spring,

Bright with flowers each shrub and tree,

From her swoon awakening

Sāmā lives, and lives for thee.

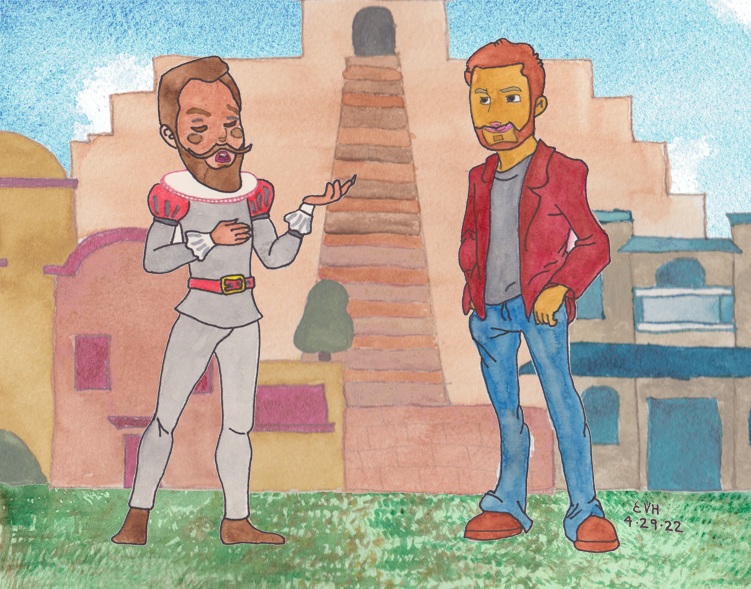

Figure: “Sāmā lives, and lives for thee.”

On hearing this the robber went up to the actor and said, “You say that Sāmā is alive, but I do not believe it.” And addressing the actor he repeated the second stanza:

Can fierce winds a mountain shake?

Can they make firm earth to quake?

But alive the dead to see

Marvel stranger far would be!

The actor on hearing these words uttered the third stanza:

Sāmā surely is not dead,

Nor another lord would wed.

Fasting from all meals but one,

She loves you and you alone.

On hearing this the robber said, “Whether she is alive or dead, I don’t want her,” and with these words he repeated the fourth stanza:

Sāmā’s fancy ever roves

From tried faith to lighter loves,

Me, too, Sāmā would betray,

Were I not to run away.

The actors came and told Sāmā how he had dealt with them. And she, full of regrets, took once more to her old course of life.

The Master, when he finished this story, taught the Four Noble Truths. At the conclusion of his teaching, the worldly-minded monk attained to fruition of the First Path (stream-entry). Then the Master identified the birth: “At that time this monk was the rich merchant’s son, the wife he had left was Sāmā, and I was the robber.”