Jataka 373

Mūsika Jātaka

The Mouse

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by H.T. Francis and R.A. Neil, Cambridge University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

This story is nearly identical to Jātaka 338 in which the Bodhisatta saves the life of a King by seeing into the future and giving him the means by which he can save himself from patricide. It is interesting that the King, when he discovers his son’s attempt to kill him, does not banish him or have him in turn killed. He lets him live to later claim the throne.

“People cry ‘Where has she gone?’” The Master told this story while he was at the Bamboo Grove (Veluvana). It is about Ajātasattu (the King of Magada who killed his father Bimbsara and conspired with Devadatta). The incident that led to the story has already been fully told in the Thusa Birth (Jātaka 338). Here, too, the Master observed the King playing with his boy and also listening to the Dharma. And knowing as he did that danger to a king will arise through his son, he said, “Sire, kings of old suspected what was open to suspicion. They kept their heirs in confinement, saying, ‘Let them rule after our bodies have burned on the funeral pyre.’” And with that he told them this story from the past.

Once upon a time during the reign of Brahmadatta, King of Benares, the Bodhisatta was born into a brahmin family. He became a world-renowned teacher. The son of the King of Benares, Prince Yava, after applying himself diligently to learning all of the liberal arts from him, was anxious to depart, so he bade him good-bye. But the teacher, knowing by his power of divination that danger would befall the Prince through his son, pondered how he might remove this danger from him. He thought about an appropriate way to demonstrate that danger.

Now at this time he had a horse, and a sore place appeared on his foot. And in order to give proper attention to the sore, the horse was kept in the stable. Now close by was a well. A mouse used to venture out of its hole and nibble the sore place on the horse’s foot. The horse could not stop it. One day he was unable to bear the pain, and when the mouse came to bite him, he struck it dead with his hoof and kicked it into the well. When the grooms did not see the mouse, they said, “On other days the mouse came and bit the sore, but now it is nowhere to be seen. What has become of it?” The Bodhisatta had witnessed the whole thing. He said, “Those who do not know what happened ask, ‘Where is the mouse?’ But I know that the mouse was killed by the horse and dropped into the well.” And making this fact an illustration, he composed the first stanza and gave it to the young Prince.

Looking about for another illustration, he saw that same horse, when the boil was healed, went out and made his way to a barley field to get some barley to eat. He thrust his head through a hole in the fence, and taking this as an illustration, he composed a second stanza and gave it to the prince.

But the third stanza he composed by his own insight and wisdom. He also gave this to him. He said, “My friend, when you are established in the kingdom, as you go in the evening to the bathing tank, walk as far as the front of the staircase, repeating the first stanza. And as you enter the palace, walk to the foot of the stairs, repeating the second stanza. And as you go to the top of the stairs, repeat the third stanza.” And with these words he dismissed him.

The young Prince returned home where he acted as a viceroy. On his father’s death, he became King. An only son was born to him. When the boy was 16 years old, he was eager to become King. He was counseled by his advisors to kill his father. He said to his retainers, “My father is still young. When I finally see his funeral pyre, I will be a worn-out old man. What good will it be for me to come to the throne then?”

“My lord,” his counselors said, “it is out of the question for you to go to the frontier and play the rebel. You must find some way to kill your father and to seize his kingdom.”

He readily agreed. In the evening, he took his sword and stood in the King’s palace near the bathing tank, prepared to kill his father. Meanwhile the King sent a female slave named Mūsikā. He said to her, “Go and clean the surface of the tank. I will take a bath.” She went there, and while she was cleaning the bath, she saw the Prince. Fearing that what he was about to do might be revealed, he cut her in two with his sword and threw the body into the tank. When the King went to bathe, everyone said, “The slave Mūsikā has not returned. Where has she gone?” The King went to the edge of the tank, repeating the first stanza:

People cry, “Where has she gone?

Mūsikā, where have you fled?”

This is known to me alone;

In the well she lies there dead.

The prince thought, “My father has found out what I have done.” And being panic-stricken, he fled and told everything to his attendants. After seven or eight days, his counselors again addressed him. They said, “My lord, if the King knew, he would not be silent. What he said must have been a guess. Put him to death.” So one day he stood—sword in hand—at the foot of the stairs. And when the King came, he looked for an opportunity to strike him. Then the King entered, repeating the second stanza:

Like a beast of burden still

You do turn and turn about,

You that Mūsikā did kill,

Fain would barley eat, I doubt.

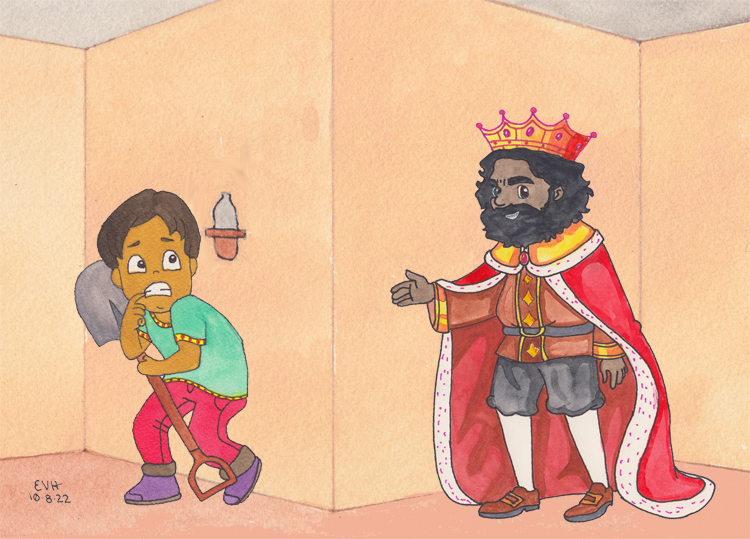

The prince thought, “My father has seen me,” and he fled in terror. But after two weeks he thought, “I will kill the King by a blow from a shovel.” So he took the spoon-like tool with a long handle and stood there raising it up. The King climbed to the top of the stair, repeating the third stanza:

You are but a weakling fool,

Like a baby with its toy,

Grasping this long spoon-like tool,

I will kill you, wretched boy.

Figure: “You are but a weakling fool.”

Unable to escape, he groveled at the King’s feet. He said, “Sire, spare my life.” The king had him bound in chains and cast into prison. And sitting on a magnificent royal seat shaded by a white parasol, he said, “My teacher, a far-famed brahmin, saw this danger to me, and he gave me these three stanzas.” And being highly delighted, in the intensity of his joy he gave forth the rest of the verses:

I am not free by dwelling in the sky,

Nor by some act of filial piety.

No, when my life was sought by this my son,

Escape from death through power of verse was won.

Knowledge of every kind he sought to learn,

And what it all may signify discern.

Though you should use it not, the time will be

When what you now hear may advantage thee.

Bye and bye, on the death of the King, the young prince was established on the throne.

The Master here brought his lesson to a close and identified the birth: “At that time I was the far-famed teacher.”