Jataka 478

Dūta Jātaka

The Emissary

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by H.T. Francis and R.A. Neil, Cambridge University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

This is a curious little tale in which the Bodhisatta is determined to pay back his teacher. When he loses his initial money, he uses his ingenuity and resourcefulness to appeal to the better nature of an otherwise somewhat stingy King!

“O plunged in thought.” The Master told this story when he was living at Jetavana. It is about praise of his wisdom. In the Dharma Hall they were gossiping, “See, brothers, the Dasabala’s (the Buddha) skill in resource! He showed that young gentleman Nanda (the Buddha’s half-brother. This story is told in Jātaka 182) the host of nymphs, and he became an arahant (fully enlightened). He gave a cloth to his little foot-page and bestowed liberation on him along with the four branches of mystic science (the four kinds of analytical knowledge: knowledge of meaning, knowledge of text, knowledge of the expression of dhamma terminology, and knowledge of those knowledges). To the blacksmith he showed a lotus and freed him. With what diverse expedients he instructs living beings!” The Master entered, and he asked what they were discussing. They told him. He said, “This is not the first time that the Tathāgata has been skilled in resourcefulness and clever to know what will have the desired effect. He was clever before as well.” And so saying, he told them this story from the past.

Once upon a time, when Brahmadatta was the King of Benares, the country was without gold because the King oppressed the country and hoarded all of the treasure. At that time the Bodhisatta was born into a brahmin family of a certain village in Kāsi. When he came of age, he went to Takkasilā University, saying, “I will get money to pay my teacher afterwards by soliciting alms honorably.” He acquired his learning, and when his education was done, he said, “I will use all diligence, my teacher, to bring you the money due for your teaching.”

Then taking leave of him, he departed. And traveling throughout the land, he sought alms. When he had honorably and fairly gotten a few ounces of gold, he set out to give them to his teacher. On the way he boarded a boat in order to cross the Ganges. As the boat swayed back and forth on the water, the gold fell in. Then he thought, “This is a country where it is hard to get gold. If I go seeking for money again to pay my teacher, there will be long delay. What if I sit fasting on the bank of the Ganges? The King will come by to learn why I am sitting here. He will send some of his courtiers, but I will have nothing to say to them. Then the King himself will come, and by that means I will get my teacher’s fee from him.”

So he wrapped his upper robe around him, and putting outside the sacrificial thread (something worn during religious ceremonies), he sat on the bank of the Ganges like a statue of gold upon the silver sand. The passing crowds, seeing him sit there and eating no food, asked him why he sat. But he never said a word to any of them. On the next day the villagers of the suburb got wind of his sitting there, and they, too, came and asked, but he told them no more. The villagers saw his exhausted condition and went away lamenting. On the third day people from the city came. On the fourth the city noblemen came. On the fifth day the King’s courtiers came, on the sixth day the King sent his ministers. But the man would not speak to any of them.

On the seventh day, the King went in alarm to the man. He asked for an explanation, reciting the first stanza:

“O plunged in thought on Ganges’ bank, why speak you not again

In answer to my messages? Will you conceal your pain?”

When he heard this, the Great Being replied, “O great King! The sorrow must be told to someone who is able to take the pain away and to no other,” and he repeated seven stanzas:

“O fostering lord of Kāsi land! If sorrow be your lot,

Tell not that sorrow to a soul if he can help it not.

“But whosoever can relieve one part of it by right,

To him let all his wish declare each sorrow-stricken plight.

“The cry of jackals or of birds is understood with ease,

Yes, but the word of men, O King, is darker far than these.

“A man may think, ‘This is my friend, my comrade, of my kin,’

But friendship goes, and often hate and enmity begin!

“He who not being asked and asked again

Out of due season will declare his pain,

Surely displeases those who are his friends,

And they who wish him well lament his bane.

“Knowing fit time for speaking how to find,

Knowing a wise man of a kindred mind,

The wise to such a one his woe declares,

In gentle words with meaning hid behind.

“But should he see that nothing can amend

His hardships, and that telling them will tend

To no good issue, let the wise alone

Endure, reserved and shamefast to the end.”

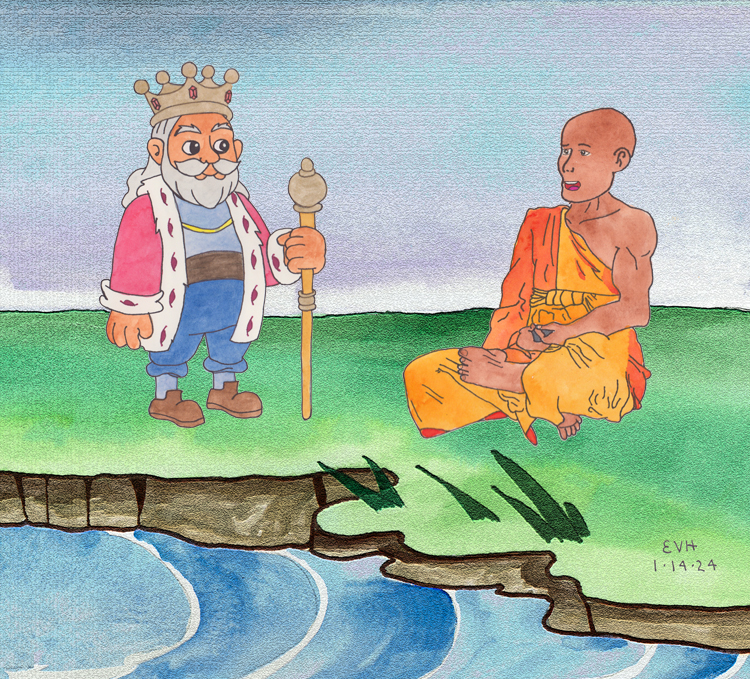

Figure: “The wise to such a one his woe declares…”

In this way the Great Being taught the King in these seven stanzas. And then he repeated four others to show his search for money to pay his teacher:

"O King! Whole kingdoms I have scoured, the cities of each king,

Each town or village, craving alms, my teacher’s fee to bring.

“Householder, courtier, man of wealth, brahmin—at every door

Seeking, a little gold I gained, an ounce or two, no more.

Now that is lost, O mighty King! And so I grieve full sore.

“No power had your messengers to free me from my pain,

I weigh’d them well, O mighty King! so I did not explain.

“But you have power, O mighty King! To free me from my pain,

For I have weighed your merit well, to you I do explain.”

When the King heard his utterance, he replied, “Trouble not, brahmin, for I will give you your teacher’s fee,” and he restored it to him two-fold.

To make this clear the Master repeated the last stanza:

“The fostering lord of Kāsi land did to this man restore

(In fullest trust) of gold refined twice what he had before.”

When the Great Being returned to his teacher, he proceeded to pay his teacher’s fee. And the King in like manner lived according to his advice, giving alms and doing good, and he ruled in righteousness. And they both finally passed away and were reborn according to their karma.

When the Master ended this discourse, he said, “So, monks, it is not only now that the Tathāgata is fertile in resources, but he was always this way.” Then he identified the birth: “At that time Ānanda was the King, Sāriputta was the teacher, and I was the young man.”