Jataka 479

Kāliṇga Bodhi Jātaka

Kāliṇga’s Bodhi Tree

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by H.T. Francis and R.A. Neil, Cambridge University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

This is a story that encompasses a part of Buddhist history, and that is planting a Bodhi tree that has sprouted from the original Bodhi tree at Bodh Gaya. It is the tree under which the Buddha attained enlightenment. Temples and monasteries all over Asia followed this custom for many centuries.

“King Kāliṅga.” The Master told this story while he was living at Jetavana. It is about reverence paid to the Bodhi tree by the Elder Ānanda.

When the Tathāgata had left on a pilgrimage for the purpose of gathering those who were ripe for conversion, the citizens of Sāvatthi went to Jetavana to see him. Their hands were full of garlands and fragrant wreaths, and finding that he had left, they laid them by the gateway of the perfumed chamber and went off. This caused great rejoicing. But Anāthapiṇḍika heard of this, and when the Tathāgata returned, he visited the Elder Ānanda and said to him, “This monastery, sir, is left unprovided while the Tathāgata goes on pilgrimage, and there is no place for the people to pay homage by offering fragrant wreaths and garlands. Will you be so kind, sir, as to tell the Tathāgata about this, and learn from him whether or not it is possible to find a place for this purpose.” Ānanda asked him, “How many shrines should there be?” “Three, Ānanda.” “Which are they?” “Shrines for a relic of the body, a relic of use or wear, and a relic of memorial” (i.e., images of the Buddha). “Can a shrine be made, sir, during your lifetime?” “No, Ānanda, not a body shrine. That kind is made when a Buddha enters Nirvāna. A shrine of memorial is improper because the connection depends on the imagination only. But the great Bodhi tree used by the Buddhas is fit for a shrine whether they are alive or dead.”

So Ānanda said to the Buddha, “Sir, while you are away on pilgrimage, the great monastery of Jetavana is unprotected, and the people have no place where they can pay homage. Shall I plant a seed of the great Bodhi tree before the gateway of Jetavana?” “By all means do so, Ānanda, and that will be a place of abiding for me.”

The Elder reported this to Anāthapiṇḍika, Visākhā (the Buddha’s primary female benefactor), and the King. Then—at the gateway of Jetavana—he cleared out a pit for the Bodhi tree. He said to the chief Elder, Moggallāna, “I want to plant a Bodhi tree in front of Jetavana. Will you get me a fruit of the great Bodhi tree?” The Elder was quite willing. He passed through the air to the platform under the Bodhi tree. He placed a fruit that was dropping from its stalk but had not reached the ground into his robe. Then he brought it back and delivered it to Ānanda. The Elder informed the King of Kosala that he was to plant the Bodhi tree that day. So in the evening the King arrived with a great retinue, bringing everything that was necessary. Then Anāthapiṇḍika and Visākhā and a crowd of the faithful came as well.

In the place where the Bodhi tree was to be planted the Elder had placed a golden jar. There was a hole in the bottom of it, and it was filled with earth moistened with fragrant water. He said, “O King, plant this seed of the Bodhi tree,” giving it to the King. But the King, thinking that his kingdom would not be in his hands forever and that Anāthapiṇḍika ought to plant it, passed the seed to the great merchant Anāthapiṇḍika. Then Anāthapiṇḍika stirred up the fragrant soil and dropped it in. The instant it dropped from his hand, before everyone’s eyes, the tree sprang up as broad as a plough head, a Bodhi tree sapling, fifty cubits tall (75 feet or about 23 meters). On the four sides and upwards shot forth five great branches of fifty cubits in length, like the trunk. So stood the tree, a very lord of the forest already, a mighty miracle! The King poured 800 jars of gold and of silver filled with scented water, decorated with a great quantity of blue water lilies around the tree. He commanded a long line of vessels—all full—to be set there. And he had a seat made of the seven precious things (gold, silver, pearl, coral, cat’s-eye, ruby, and diamond). He had gold dust sprinkled around it. A wall was built around the precincts. He erected a gate chamber of the seven precious things, and great honor was paid to it.

The Elder approached the Tathāgata. He said to him, “Sir, for the peoples’ good, accomplish under the Bodhi tree that I have planted that state you attained under the great Bodhi tree.” “What is this you say, Ānanda?” he replied. “There is no other place that can support me if I sit there and attain that which I attained in the enclosure of the great Bodhi tree.” “Sir,” said Ānanda, “I pray to you for the good of the people, use this tree for the rapture of Attainment in so far as this spot of ground can support the weight.” And so the Master used it during one night for the rapture of Attainment.

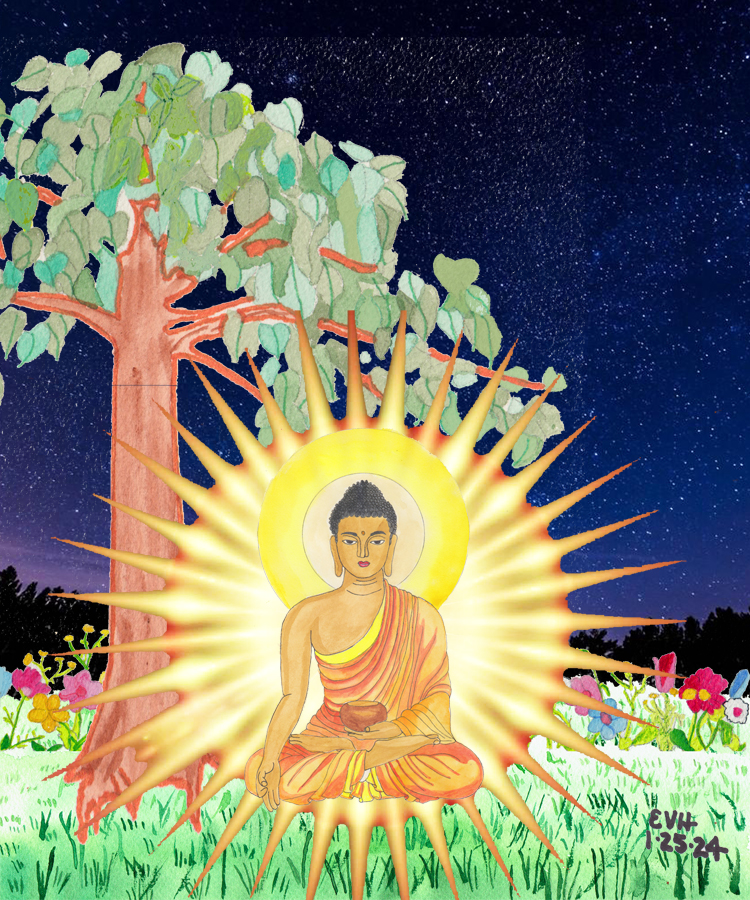

Figure: The rapture of Attainment

The Elder informed the King and all the rest what had occurred, and he called it the Bodhi Festival. And this tree, having been planted because of Ānanda, was known as Ānanda’s Bodhi Tree.

They began to discuss this event in the Dharma Hall. “Brother, while yet the Tathāgata lived, the venerable Ānanda caused a Bodhi tree to be planted and great reverence paid to it. Oh, how great is the Elder’s power!” The Master entered and asked what they were discussing. They told him. He said, “This is not the first time, monks, that Ānanda caused a vast quantity of scented wreaths to be brought and made a Bodhi festival in the precinct of the great Bodhi tree.” And so saying, he told them this story from the past.

Once upon a time in the kingdom of Kāliṅga and in the city of Dantapura, there reigned a King named Kāliṅga. He had two sons. One was named Mahā-Kāliṅga—Kāliṅga the Senior—and Culla-Kāliṅga, or Kāliṅga the Younger. Now fortune tellers had foretold that the eldest son would reign after his father’s death, but the youngest would live as a recluse. He would live on alms, but his son would become a universal monarch.

Time passed, and on his father’s death the eldest son became King. The younger son became his viceroy. But the youngest, thinking that a son born of him was to be a universal monarch, grew arrogant. The King could not abide this, so he sent a messenger to arrest Kāliṅga the Younger. The messenger arrived, and he said, “Prince, the King wishes to have you arrested, so save your life.” The Prince showed the courtier charged with this mission his own signet ring, a fine rug, and his sword. Then he said, “By these tokens you will know my son and make him King.” With these words, he fled into the forest. There he built a hut in a pleasant place and lived as a recluse on the bank of a river.

Now in the kingdom of Madda, in the city of Sāgala, a daughter was born to the King of Madda. As with the Prince, fortunetellers foretold that she should live as a recluse and that her son was to be a universal monarch. The Kings of India, hearing this rumor, gathered together to be her suitor, and they surrounded the city. The King thought to himself, “Now, if I give my daughter to one of them, all the other kings will be enraged. I will try to save her.” So with his wife and daughter, he fled disguised into the forest. And after building a hut some distance up the river—above the hut of Prince Kāliṅga—he lived there as a recluse, eating what he could forage.

One day the parents left her behind in the hut and went out to gather wild fruits. While they were gone, she gathered flowers of all kinds and made them into a flower wreath. Now on the bank of the Ganges there is a mango tree with beautiful flowers that forms a kind of natural ladder. She climbed up this, and while she was playing, she dropped the wreath of flowers into the water.

One day, as Prince Kāliṅga was coming out of the river after a bath, this flower wreath caught in his hair. He looked at it and said, “Some woman made this, and not a full-grown woman but a tender young girl. I must search for her.” So deeply in love, he journeyed up the Ganges until he heard her singing in a sweet voice as she sat in the mango tree. He approached the foot of the tree, and seeing her, he said, “What are you, fair lady?” “I am human, sir,” she replied. “Come down, then,” he said. “Sir, I cannot. I am of the warrior caste (khatiyā).” “So am I, lady. Come down!” “No, no, sir. That I cannot do. Saying so does not make you a warrior. If you are, tell me the secrets of that mystery.” Then they repeated to each other the caste secrets. And so the princess came down, and they had an attraction to one another.

When her parents returned she told them about this son of the King of Kālinga and how he came into the forest. They agreed to give her to him. They lived together in a happy union, and finally the Princess conceived. After ten months she gave birth to a son with the signs of good luck and virtue, and they named him Kāliṅga. He grew up and learned all the arts and accomplishments from his father and grandfather.

At length his father knew from a conjunction of the stars that his brother was dead. So he called his son and said, “My son, you must not spend your life in the forest. Your father’s brother, Kāliṅga the Senior, is dead. You must go to Dantapura and receive your hereditary kingdom.” Then he gave him the things he had brought away with him—the signet ring, the rug, and the sword—saying, “My son, in the city of Dantapura, on a certain street, there lives a courtier who is my very good servant. Go into his house. Enter his bedchamber and show him these three things. Tell him you are my son. He will place you on the throne.”

The lad bade farewell to his parents and grandparents, and by the power of his virtue, he flew through the air. And descending into the house of that courtier, he entered his bedchamber. “Who are you?” asked the courtier. “The son of Kāliṅga the Younger,” he said, showing him the three tokens. The courtier reported this to the palace, and all those of the court decorated the city and spread the umbrella of royalty over his head. Then the chaplain, who was named Kāliṅga-bhāradvāja, taught him the ten ceremonies that a universal monarch has to perform, and he fulfilled those duties. Then on the fifteenth day, the fast day, he presented to him the precious Wheel of Empire from Cakkadaha. He gave him a precious elephant from the Uposatha stock. From the royal Valāha breed he was given a precious horse, and from Vepulla the precious jewel. Then the precious wife, retinue, and Prince made their appearance, and he achieved sovereignty over the whole terrestrial sphere.

One day, surrounded by a company which covered six-and-thirty leagues (over 2,000 miles or 3600 kilometers), and mounted on an all-white elephant as tall as a peak of Mount Kelāsa, he went to visit his parents in great pomp and splendor. But beyond the circuit around the great Bodhi tree, the throne of victory of all the Buddhas, which has become the very navel of the earth, beyond this the elephant was not able to pass: again and again the King urged him on, but he could not pass it.

Explaining this, the Master recited the first stanza:

“King Kāliṅga, lord supreme,

Ruled the earth by law and right,

To Bodhi tree once he came

On an elephant of might.”

The King’s chaplain, who was travelling with the King, thought to himself, “There is no hindrance in the air. Why can’t the King make his elephant go on? I will go and see.” Then descending from the air, he beheld the throne of victory of all Buddhas, the navel of the earth, that circuit around the great Bodhi tree. At that time, it is said, for the space of a royal karísa (about an acre) there was not a single blade of grass, not even one as big as a hare’s whisker. It seemed as if it were spread smooth with sand as bright as a silver plate. Yet on all sides there was grass. There were creepers and mighty trees like the lords of the forest, as though standing in reverence wise all about with their faces turned towards the throne of the Bodhi tree. When the brahmin saw this spot of earth he thought, “This is the place where all the Buddhas have crushed the desires of the flesh. Beyond this no one can pass, not even Sakka himself.” Then approaching the King, he told him the nature of the Bodhi tree circuit and told him to descend.

Figure: “Beyond this no one can pass, not even Sakka himself.”

By way of explaining this the Master recited these stanzas following:

“This Kāliṅga-bhāradvāja told his King, the recluse’s son,

As he rolled the wheel of empire, guiding him, obeisance done.

“This the place the poets sing of here, O mighty King, alight!

Here attained to perfect wisdom perfect Buddhas, shining bright.

“In the world, tradition has it, this one spot is hallowed ground,

Where in attitude of reverence herbs and creepers stand around.

“Come, descend and do obeisance, since as far as the ocean bound

In the fertile earth all-fostering this one spot is hallowed ground.

“All the elephants you do own thoroughbred by dam and sire,

Drive them to here, they will surely come this far, but come no nigher.

“He is thoroughbred you ride on, drive the creature as you will,

He can go not one step further. Here the elephant stands still.”

“Spoke the soothsayer, heard Kāliṅga, then the King to him, quote he,

Driving deep the goad into him—'Be this truth, we soon shall see.’

“Pierced, the creature trumpets loudly, shrill as any heron cries,

Moved, then fell upon his haunches neath the weight, and could not rise.”

Pierced and pierced again by the King, this elephant could not endure the pain, and so he died. But the King did not know that he was dead and still sat there on his back. Then Kāliṅga-bhāradvāja said, “O great King! Your elephant is dead. Mount yourself on another.”

To explain this matter, the Master recited the tenth stanza:

“When Kāliṅga-bhāradvāja saw the elephant was dead,

He in fear and trepidation then to King Kāliṅga said,

‘Seek another, mighty monarch. This your elephant is dead.’”

By the virtue and magical power of the King, another beast of the Uposatha breed appeared and offered his back. The King mounted him, and at that moment the dead elephant fell onto the earth.

To explain this matter, the Master repeated another stanza:

“This heard, Kāliṅga in dismay

Mounted another, and straightway

Upon the earth the corpse sank down,

And the soothsayer’s word for very truth was shown.”

Thereupon the King came down from the air, and beholding the precinct of the Bodhi tree and the miracle that was done, he praised Bhāradvāja, saying:

“To Kāliṅga-bhāradvāja King Kāliṅga did say,

“You know all and do understand, and you see all away.”

Now the brahmin would not accept this praise. But standing in his own humble place, he extolled the Buddhas and praised them.

To explain this, the Master repeated these stanzas:

“But the brahmin straight denied it, and did say unto the King,

‘I know about marks and tokens, but the Buddhas, everything.

‘Though all-knowing and all-seeing, yet in marks they have no skill.

‘They know all, but know by insight. I am a man of books still.’”

The King, hearing the virtues of the Buddhas, was delighted in his heart. He caused all the dwellers in the world to bring fragrant wreaths in plenty, and for seven days he made them pay homage at the circuit of the great Bodhi tree.

By way of explanation, the Master recited a couple of stanzas:

"Thus he worshipped the Bodhi tree with much melodious sound

Of music, and with fragrant wreaths, a wall he set around.

“And after that the King went on his way—

“Brought flowers in sixty thousand carts an offering to be,

Thus King Kāliṅga worshipped the Circuit of the Tree.”

Having paid homage in this way to the great Bodhi tree, he visited his parents. He took them back with him again to Dantapura. There he gave alms and did good deeds until he was born again in the Heaven of the Thirty-Three.

The Master, having finished this discourse, said, “Now is not the first time, monks, that Ānanda did worship the Bodhi tree, but he did so in the past as well.” Then he identified the birth: “At that time Ānanda was Kāliṅga, and I was Kāliṅga-bhāradvāja.”