Jataka 488

Bhisa Jātaka

The Lotus Root

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by H.T. Francis and R.A. Neil, Cambridge University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

Many of these stories have simple themes. But when you live with them every day in the way in which they were with people who lived in Buddhist cultures, they seep into your bones. The norm becomes to be kind, and cultivating that kindness becomes a lifetime’s work.

“May horse and cow.” The Master told this story while he was living at Jetavana. It is about a backsliding monk. The circumstances will appear under the Kusa Birth (Jātaka 530). Here again the Master asked, “Is it true, brother, that you have backslidden?” “Yes, sir, it is true.” “Why is that?” “For sense desire’s sake, sir.” “Brother, why do you backslide after embracing a faith such as this that leads to liberation, and all for the sake of sensual pleasures? In days gone by, before the Buddha arose, wise men who took to the holy life, even they who were beyond any authority, made an oath and renounced ideas connected with temptations or sensual desires!” So saying, he told this story of the past.

Once upon a time, when Brahmadatta was the King in Benares, the Bodhisatta was born as the son of a powerful brahmin who owned a fortune of 80 crores of money (1 crore equals 10 million rupees). They named him Lord Mahā-Kañcana, the Greater Lord of Gold. When he began to walk, another son was born to the brahmin. They called him Lord Upa-Kañcana, the Lesser Lord of Gold. Thus, in succession seven sons were born, and youngest of all came a daughter. They named her Kañcana-devī, the Lady of Gold.

When Mahā-Kañcana came of age, he studied the arts and sciences at Takkasilā University, and then he returned home. His parents wanted him to establish him a household of his own. “We will find you,” they said, “a girl from a family to be a good match for you, and then you will have your own household.” But he said, “Mother and father, I do not want a household. To me the three kinds of existence (1. Kama Loka—the world of sensuality—in which humans, animals, and some devas reside, 2. Rupadhatu Loka—the world of material existence—in which certain beings mastering specific meditative attainments reside, and 3. Arupadhatu Loka—the immaterial, formless world—in which formless spirits reside) are as terrible as fires. They are beset with chains like a prison, as loathsome as a dunghill. I have never known deeds of those kinds, not so much as in a dream. You have other sons, urge them to be the heads of families and leave me alone.”

Even though they begged him repeatedly, even sending his friends to him and begging him with their words, he would have none of it. Then his friends asked him, “What do you want, my good friend, that you care nothing for the enjoyment of love and desire?” He told them that he had renounced the ordinary world. Once his parents understood this, they made similar proposals to the other sons, but none of them would hear of it either. Not even the Lady Kañcanā was interested in the sensory world.

By and by the parents died. The wise Mahā-Kañcana did the funeral ceremony for his parents. He distributed the treasure of 80 crores to beggars and wayfaring men as alms. Then he took his six brothers, his sister, a servant man and handmaiden, and one companion with him, and he retired into the Himalaya Mountains. There they built a hermitage in a delightful spot near a lotus lake. They lived a holy life eating the fruits and roots of the forest. When they went into the forest, they went one by one, and if ever one of them saw a fruit or a leaf he would call the rest. Telling all they saw and heard, they picked up what there was. It seemed like the village market.

But the teacher, the ascetic Mahā-Kañcana, thought to himself, “We have cast aside a fortune of 80 crores and taken up the holy life, and to go about greedily seeking for wild fruits is unsuitable. From now on I will bring the wild fruits by myself.” Returning to the hermitage, in the evening he gathered everyone together and told them his thought. “You remain here,” he said, “and practice the life of the recluse. I will fetch fruit for you.” Upa-Kañcana and all the rest broke in. “We have become holy under your influence. It is you who should stay behind and practice the life of the recluse. Let our sister remain here, also, and the maid be with her. The eight of us will take turns gathering the fruit, but you three shall be free from taking a turn.”

He agreed. From then they each took their turns bringing in fruit one at a time. Everyone received a share of the find. They each carried it off to a dwelling place and remained in their own leaf-hut. In this way they could not be together without cause or reason. He whose turn it was would bring in the food, laying it on a flat stone, and making eleven portions. Then ringing the gong, he would take his own portion and depart to his hut. The others would assemble without hurrying, with all due ceremony and order. Each one would take his allotted portion, then return to his own place and eat it there. Then they would resume meditating and practice holy austerity. After a time, they gathered lotus fibers and ate them. And there they lived, enduring scorching heat and other kind of torments, their senses all dead, striving to attain the ecstatic trance of deep samadhi.

By the glory of their virtue Sakka’s throne trembled. “Are these released from sensual desire only,” he said, “or are they sages? Are they sages? I will find out now.” So using his supernatural power, for three days he caused the Great Being’s share of food to disappear. On the first day, seeing no food, he thought, “My share must have been forgotten.” On the second day he thought, “There must be some fault in me. He has not provided my share in the way of due respect.” On the third day he said, “Why can there be no share for me? If there is a fault in me, I will make my peace.”

So in the evening he rang the gong. They all came together and asked who had sounded the gong. “I did, my brothers.” “Why, good Master?” “My brothers, who brought in the food three days ago?” One got up and said, “I did,” standing with all due respect. "When you made the division, did you set apart a share for me?” “Why yes, Master, the share of the eldest.” “And who brought food yesterday?” Another rose, and said, “I did,” then stood respectfully. “Did you remember me?” “I put by the share of the eldest for you.” “Today who brought the food?” Another rose and stood respectfully. “Did you remember me in making the division?” “I set aside the share of the eldest for you.” Then he said, “This is the third day I have had no share of food. The first day when I saw none, I thought, ‘Doubtless whoever made the division has forgotten my share.’ On the second day, I thought there must be some fault in me. But today I made up my mind that if there were a fault, I would make my peace. Therefore, I summoned you by the sound of this gong. You tell me you have put aside these portions of the lotus fibers for me, but I have had none of them. I must find out who has stolen and eaten these. When one has forsaken the world and all its lusts, theft is unseemly, even if it is no more than a lotus stalk.” When they heard these words, they cried out, “Oh what a cruel deed!” and they were all disturbed.

Now the deity that lived in a tree by that hermitage, the greatest tree of the forest, came out and sat down in their midst. There was also an elephant whose training had proven to be impossible. He had broken the stake to which he was bound and escaped into the woods. From time to time he used to come and salute the band of sages. Now he came as well and stood on one side. There was also a monkey there. He had been used as a sport for snakes. He had escaped out of the snake charmer’s hands and escaped into the forest. Now he lived in that hermitage, and on that day he also greeted the band of recluses, then he stood on one side. Sakka was determined to test the sages. He was there, but he was invisible.

At that moment the Bodhisatta’s younger brother, the recluse Upa-Kañcana, rose up from his seat and saluted the Buddha. With a bow to the rest of the company, he said, “Master, setting aside the others, may I clear myself of this charge?” “You may, brother.” He stood amid the sages and made a solemn oath in the first stanza:

“May horse and cow be his, may silver, gold,

A loving wife, these may he precious hold,

May he have sons and daughters manifold,

Brahmin, who stole your share of food away.”

On this the recluses put their hands over their ears, crying, “No, no, sir, that oath is very heavy!” And the Bodhisatta also said, “Brother, your oath is very heavy. You did not eat the food. Sit down on your cushion.” Having made his oath, he sat down.

The second brother stood, and saluting the Great Being, he recited the second stanza to clear himself:

“May he have sons and raiment at his will,

Garlands and sandal sweet his hands may fill,

His heart be fierce with lust and longing still,

Brahmin, who stole your share of food away.”

When he sat down, the others—each in turn—uttered his own stanza to express his feeling:

“May he have plenty, win both fame and land,

Sons, houses, treasures, all at his command,

The passing years may he not understand,

Brahmin, who stole your share of food away.”

“As mighty warrior chief may he be known,

As king of kings set on a glorious throne,

The earth and its four corners all his own,

Brahmin, who stole your share of food away.”

“Be he a brahmin, passion unsubdued,

With faith in stars and lucky days imbued,

Honored with mighty monarchs’ gratitude,

Brahmin, who stole your share of food away.”

“A student in the Vedic lore deep-read,

Let all men reverence his holy head,

And of the people be he worshipped,

Brahmin, who stole your share of food away.”

“By Indra's gift a village may he hold,

Rich, choice, possessed of all the goods fourfold,

And may he die with passions uncontrolled,

Brahmin, who stole your share of food away."

(The fourfold goods are 1. well-populated, 2. rich in grain, 3. Rich in wood, 4. rich in water.)

“A village chief, his comrades all around,

His joy in dances and sweet music’s sound,

May the king’s favor unto him abound,

Brahmin, who stole your share of food away.”

“May she be fairest of all womankind,

May the high monarch of the whole world find,

Her chief among ten thousand to his mind,

Brahmin, who stole your share of food away.”

“When all the serving handmaidens do meet,

May she all unabashed sit in her seat,

Proud of her gains, and may her food be sweet.

Brahmin, who stole your share of food away.”

“The great Kajañgal cloister be his care,

And may he set the ruins in repair,

And every day make a new window there,

Brahmin, who stole your share of food away.”

(This verse was spoken by the tree-spirit. Kajañgala was a town where materials were hard to be got. In Buddha Kassapa's time a god had a hard job repairing the ruins of an old monastery.)

“Fast in six hundred bonds may he be caught,

From the dear forest to a city brought,

Smitten with goads and guiding-pikes, distraught,

Brahmin, who stole your share of food away.”

“Garland on neck, tin earring in each ear,

Bound, let him walk the highway, much in fear,

And schooled with sticks to serpent kind draw near,

Brahmin, who stole your share of food away."

When each of the 13 had taken an oath, the Great Being thought, “Perhaps they imagine I am lying myself and saying that the food was not there when it was.” So he made oath on his part in the fourteenth stanza:

“Who swears the food was gone, if it was not,

Let him enjoy desire and its effect,

May worldly death be at the last his lot.

The same for you, sirs, if you now suspect.”

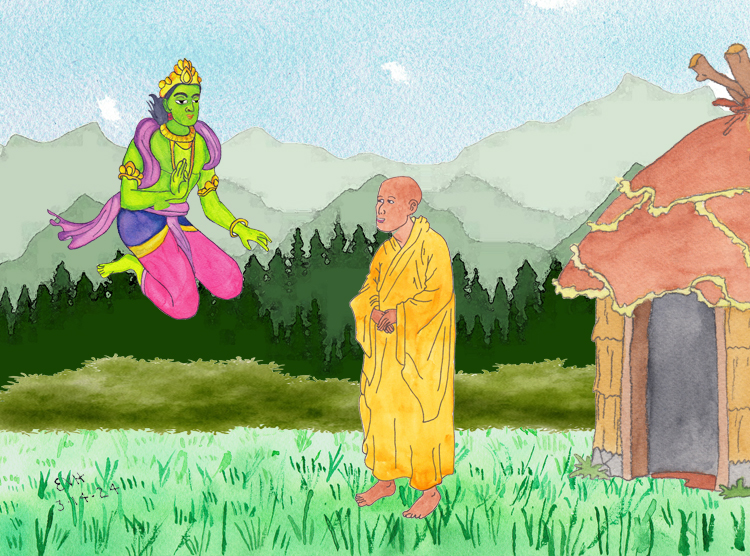

When the sages had all made their oaths, Sakka thought to himself, “Fear nothing. I made these lotus fibers disappear to test these sages. But they all make an oath, loathing the deed as if it were a snot of spittle. Now I will ask them why they loathe lust and desire.” He put this question to the Bodhisatta in the next stanza, after having assumed a visible form:

“What in the world men go a-seeking here

That thing to many lovely is and dear,

Longed-for, delightful in this life, why, then,

Have saints no praise for things desired of men?”

By way of answer to this question, the Great Being recited two stanzas:

“Desires are deadly blows and chains to bind,

In these both misery and fear we find,

When tempted by desires imperial kings

Infatuate do vile and dreadful things.

The wicked bring misdeeds, to hell they go

At dissolution of this mortal frame.

Because the misery of lust they know

Therefore saints praise not lust, but only blame.”

When Sakka heard the Great Being’s explanation, his heart was moved. He repeated the following stanza:

“To test these sages I did steal away

That food, which by the lake side I did lay.

Sages they are indeed and pure and good.

O man of holy life, behold your food!”

Hearing which the Bodhisatta recited a stanza:

“We are no tumblers, to make sport for thee,

No kinsmen nor no friends of yours are we.

Then why, O king divine, O thousand-eyed,

Think you the sages must your sport provide?”

And Sakka recited the twentieth stanza, making his peace with him:

“You are my teacher, and my father thou,

From my offence let this protect me now.

Forgive me my one error, O wise sage!

They who are wise are never fierce in rage.”

Figure: “You are my teacher…”

Then the Great Being forgave Sakka, king of the gods. And on his own part to reconcile him with the company of sages, he recited another stanza:

“Happy for holy men one night has been,

When the Lord Vāsava by us was seen.

And, sirs, be happy all in heart to see

The food once stolen now restored to me.”

(Vāsava is a pseudonym for Indra/Sakka/Śakra.)

Sakka saluted the company of sages and returned to the world of gods. The sages attained deep samadhi, and they became destined for Brahma’s world.

When the Master had ended this discourse, he said, “Thus, monastics, wise men of old made an oath and renounced misdeeds.” This said, he taught the Four Noble Truths. At the conclusion of the teaching, the backsliding brother was established in the fruit of the First Path (stream-entry). Then—identifying the birth—he recited three stanzas:

“Sāriputta, Moggallāna, Puṇṇa, Kassapa, and I,

Anuruddha and Ānanda then the seven brothers were.

“Uppalavaṇṇā was the sister, and Khujjuttarā the maid,

Sātāgira was the spirit, Citta householder the slave.

“The elephant was Pārileyya, Madhuvāseṭṭha was the ape,

Kāḷudāyi then was Sakka. Now you understand the birth.”

(Sāriputta, Moggallāna, Puṇṇa, Kassapa, Anuruddha and Ānanda were disciples of the Buddha. Uppalavaṇṇā was one of the Buddha’s foremost nuns. Sātāgira was a Yakkha who was known for praising the Buddha. Citta was one of the Buddha’s foremost lay disciples. Pārileyya is an elephant who once cared for the Buddha. Madhuvāseṭṭha as an ape and a follower of the Buddha. Kāḷudāyi was a minister’s son and a contemporary of the Buddha.)