Jataka 538

Mūga Pakkha Jātaka

The Dumb Cripple

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by H.T. Francis and R.A. Neil, Cambridge University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

This is a long story in which the Bodhisatta is reborn as a prince. But he remembers having been a king in a previous life. In that life he administered some harsh penalties on people, and for that he spent 80,000 years in hell. Yikes! So in this life he does everything he can to avoid being king again.

If you have been following along all these Jātaka Tales, you will have seen the theme of kings and royalty and others becoming renunciates. It is an interesting and counterintuitive way to think about life. In the West we usually celebrate fame and wealth and power and “success.” But in the Dharma, success is measured by your virtue. Renunciates choose to live simple lives. Materially they live lives of poverty and scarcity. But they live lives that are spiritually rich. On a worldly level, happiness is generated by virtue. On the transcendent level, happiness is generated from deep meditation, samadhi. And ultimately happiness comes from being free from saṃsara and the rounds of rebirth.

“Show no intelligence.” The Master told this story at Jetavana. It is about the great renunciation. One day the monks were seated in the Dharma Hall. They were praising the Blessed One’s great renunciation. When the Master came and asked the monks what was the topic of their discussion. When he heard what it was, he said, “No, brothers. my renunciation of the world, after leaving my kingdom, was not wonderful. I had fully developed the perfections. Before, even when my wisdom was still immature and while I was cultivating the perfections, I left my kingdom and renounced the world.” And at their request, he told them this story from the past.

Once upon a time a king—Kāsirājā—ruled justly in Benares. He had 16,000 wives, but not one among them conceived either a son or a daughter. The citizens assembled—as in the Kusa Jātaka (Jātaka 531)—and said, “Our king has no son to keep up his line.” They begged the king to pray for a son. The king commanded his 16,000 wives to pray for sons. But although they worshipped the moon and the other deities and prayed, they obtained none.

Now his chief queen Candādevī, the daughter of the king of the Maddas, was devoted to good works. He asked her also to pray for a son. So on the day of the full moon, she took the Uposatha vows (Eight Precepts), and while lying on a little bed, she reflected on her virtuous life. She made an Act of Truth in these terms: “If I have never broken the Precepts, by the truth of this my declaration may a son be born to me.”

Through the power of her piety, Sakka’s dwelling became hot. Sakka, having considered and determined the cause, said, “Candādevī asks for a son. I will give her one.” And as he looked for a suitable son, he saw the Bodhisatta.

Now the Bodhisatta, after having reigned 20 years in Benares, had been reborn in the Ussada hell where he had suffered for 80,000 years. (Ussada was a “minor hell.” It was considered a place of great suffering. It was also a place for those who promised a gift but failed to give it. Beings born there have their tongues pierced with glowing hooks and are dragged about on a floor of heated metal. It’s a bad place.) Then he had been born in the world of the thirty-three gods, and after having stayed there for his allotted time, he had passed away from there and wanted to go to the world of the higher gods. But Sakka went up to him and said, “Friend, if you are born in the world of men, you will fully develop the perfections, and the whole of mankind will benefit. Now this chief queen of Kāsirājā, Candā, is praying for a son. Will you be conceived in her womb?” He consented.

He arrived attended by 500 deities and was conceived in her womb. The other deities were conceived in the wombs of the wives of the king’s ministers. The queen’s womb seemed to be full of treasure. When she became aware that she was pregnant, she told the king. He had every precaution taken for the safety of the unborn child.

At last she brought forth a son. He was covered with auspicious marks. On that same day 500 young nobles were born in the ministers’ houses. The king was seated on his royal dais surrounded by his ministers when it was announced, “A son is born to you, O king.” When he heard this, paternal affection arose and pierced his skin. It reached the marrow in his bones. Joy sprang up in him and his heart became refreshed. He asked his ministers, “Are you happy at the birth of my son?” “What are you saying, sire?” they answered. “Before we were helpless. Now we have a help. We have obtained a lord.” The king gave orders to his chief general, “A retinue must be prepared for my son. Find out how many young nobles have been born today in the ministers’ houses.” He saw the 500 and went and told this to the king.

The king sent princely clothing of honor for the 500 young nobles, and he also sent 500 nurses. He provided 64 nurses for the Bodhisatta. They were all free from the faults of being too tall, with their breasts not hanging down, and full of sweet milk. If a child drinks milk sitting on the hip of a nurse who is too tall, its neck will become too long. If it sits on the hip of one too short, its shoulder bone will be compressed. If the nurse is too thin, the baby’s thighs will ache. If the nurse is too stout, the baby will become bow-legged. The body of a very dark nurse is too cold. The body of a white one is too hot. Children who drink the milk of a nurse with hanging breasts have the ends of their noses flattened. Some nurses have sour milk. Others have it bitter. Therefore, avoiding all these faults, he provided 64 nurses. They all possessed sweet milk and were without any of these faults.

After paying the Bodhisatta great honor, he also gave the queen a boon. She accepted it and kept it in her mind. On his naming day, they paid great honor to the brahmans who read the different marks. He asked if there was any danger lurking. Beholding the excellence of his marks, they replied, “O king, the prince possesses every mark of future good fortune. He can rule not only one continent but all the four. There is no danger visible.” The king was pleased. He gave him the name Temiyakumāro, since it had rained all over the kingdom of Kāsī on the day of his birth and he had been born wet. (It is not clear what the name means. “Kumāro” means “prince.” “Temiya” may be a derivative of “temita” which means “moist.”)

When he was one month old, they adorned him and brought him to the king. When the king looked at his dear child, he embraced him. He placed him on his hip and sat playing with him. Now at that time four robbers were brought before him. He sentenced one of them to receive a thousand strokes from whips barbed with thorns. Another one he sentenced to be imprisoned in chains. A third one he sentenced to be beaten with a spear, and the fourth one he ordered to be impaled. When he heard his father’s words, the Bodhisatta was terrified. He thought to himself, “Ah! Because my father is powerful, he is guilty of a grievous action that brings men to hell.”

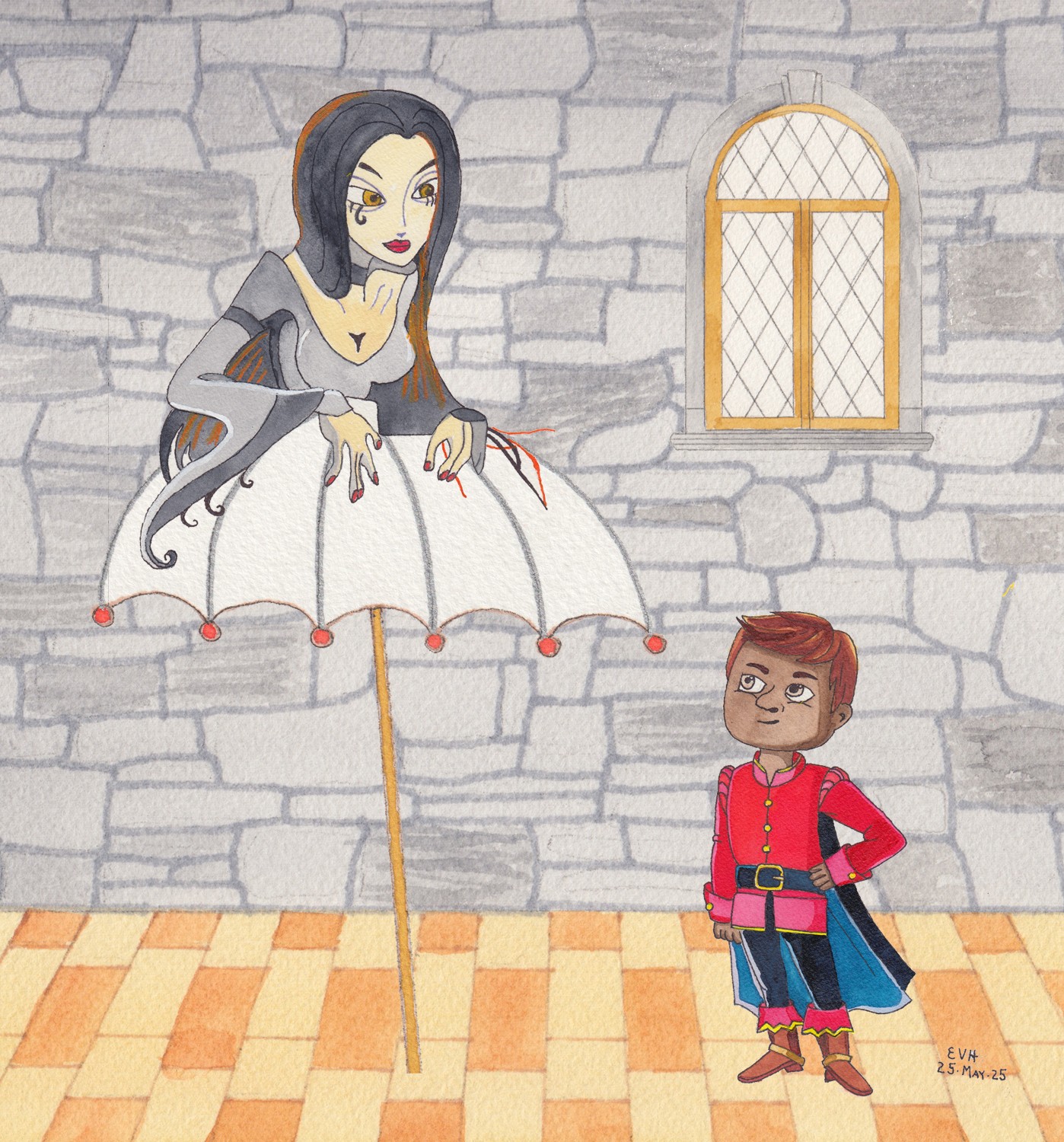

On the next day they laid him on a sumptuous bed under a white umbrella. He awoke after a short sleep and opened his eyes. He saw the white umbrella and the royal pomp, and his fear increased even more. As he be pondered “from where have I come into this palace?” he remembered his former births. He remembered that he had once come from the world of the gods, and that after that he had suffered in hell, and that before that he had been a king in that very city. He remembered, “I was a king for 20 years and then I suffered 80,000 years in the Ussada hell. Now, again, I am born in this house of robbers. And my father, when four robbers were brought before him, uttered a cruel speech that must lead to hell. If I become a king, I will be born again in hell and suffer great pain there.” He was greatly alarmed. His golden body became pale and faded like a lotus crushed by the hand. He lay there thinking how he could escape from that house of robbers.

Then a goddess who lived in the umbrella and who in a previous birth had been his mother, comforted him. “Fear not, my child Temiya. If you really want to escape, pretend to be a cripple although you are not. Though you are not deaf, pretend to be deaf. And though you are not dumb, pretend to be dumb. Show these traits and show no signs of intelligence.” Then she uttered the first stanza,

“Show no intelligence, my child, be as a fool in all men’s eyes,

Content to be the scorn of all, thus shall you gain at last the prize.”

Figure: The umbrella spirit advises Temiya

Being comforted by her words he uttered the second stanza,

“O goddess, I will do your will, what you command for me is best,

Mother, you wish for my well-being, you long but to see me blessed.”

And so he practiced these three characteristics.

To cheer up his son, the king had the 500 young nobles brought to him. The children began crying for their milk. But the Bodhisatta was afraid of hell. He reflected that to die of thirst would be better than to reign, and so he did not cry. The nurses told this to Queen Candā, and she told it to the king. He sent for some brahmans who were skilled in signs and omens, and he consulted them. They replied, “Sire, you must give the prince his milk after the proper time has passed. He will then cry and seize the breast eagerly and drink of his own accord.” So they gave him his milk after letting the proper time pass by. Sometimes they let it pass by once. Sometimes they did not give it to him all day. But he was so stung by the fear of hell that even though he was thirsty, would not cry for milk.

Then the mother or the nurses gave him milk, even though he did not cry for it. They said, “The boy is famished.” The other children cried when they did not get their milk, but he neither cried nor slept nor doubled up his hands nor feet nor would he hear a sound. Then his nurses reflected, “The hands and feet of cripples are not like his. The formation of the jaws of the dumb is not like his. The structure of the ears of the deaf is not like his. There must be some reason for all this. Let us examine into it.”

For one whole day they gave him no milk. And even though he was parched, he uttered no sound for milk. Then his mother said, “My boy is famished. Give him milk,” and she made them give him milk. In this way, giving him milk at intervals, they spent a year testing him. But they did not discover his weak point. They said, “The other children are fond of cakes and dainties. We will try them with him.” They put the 500 children near him and brought various dainties. They placed them close by him, and then they hid themselves. The other children quarreled and struck one another and seized the cakes and ate them. But the Bodhisatta said to himself, “O Temiya, eat the cakes and dainties if you wish to go to hell.” In his fear of hell, he would not even look at them. So, even though they tested him with cakes and dainties for a whole year, they did not discover his weak point.

Then they said, “Children are fond of different kinds of fruit.” They brought all sorts of fruit and tested him. The other children fought for them and ate them, but he would not even look at them. For a whole year they tested him with various kinds of fruit. Then they said, “Other children are fond of playthings.” So, they set golden and other figures of elephants near him. The rest of the children seized them as if they were spoils, but the Bodhisatta would not even look at them. And thus, for a whole year they tested him with playthings.

Then they said, “There is a special food for children four years old. We will test him with that.” They brought all sorts of food. The other children broke them in pieces and ate them. But the Bodhisatta said to himself, “O Temiya, there is no counting the past births when you did not obtain food.” And because of his fear of hell, he did not look at them. At last his mother, with her heart nearly broken, fed him with her own hand.

Then they said, “Children five years old are afraid of fire. We will test him with that.” So, they had a large house built with many doors. It was covered over with palm leaves. They set him in the middle of it surrounded by the other children. Then they set fire to it. The others ran away shrieking, but the Bodhisatta said to himself that it was better than the torture in hell. He remained motionless, as if perfectly apathetic. When the fire came near him, they took him away. Then they said, “Children six years old are afraid of wild elephants.” So they had a well-trained elephant taught, and, when they had seated the Bodhisatta with the other children in the palace court, they let it loose. It came trumpeting and striking the ground with its trunk and spreading terror. The other children fled in all directions in fear for their lives. But the Bodhisatta, being afraid of hell, sat where he was. The well-trained animal took him and lifted him up and down and went away without hurting him.

When he was seven years old, as he was sitting surrounded by his companions, they let loose some snakes with their teeth extracted and their mouths bound. The other children ran away shrieking. But the Bodhisatta, remembering the fear of hell, remained motionless. He said, “It is better to perish by the mouth of a fierce serpent.” Then the snakes enveloped his whole body. They spread their hoods on his head, but still he remained motionless. Thus, though they tested him again and again, they still could not discover his weak point.

Then they said, “Boys are fond of social gatherings.” So they set him in the palace court with the 500 boys. They had an assembly of mimes gathered. The other boys watched the mimes. They shouted “bravo” and laughed loudly. But the Bodhisatta, saying to himself that if he were born in hell there would never be a moment’s laughter or joy, remained motionless. He never looked at their dancing. Thus, trying him again and again they discovered no weak point in him.

Then they said, “We will test him with the sword.” They placed him with the other boys in the palace court. While they were playing, a man rushed upon them. He brandished a sword like crystal. He shouted and jumped, and he said, “Where is this devil’s child of the King of Kāsī? I will cut off his head.” The others fled, shrieking in terror at the sight of him. But the Bodhisatta, having reflected on the fear of hell, sat as if unconscious. The man, although he rubbed the sword on his head and threatened to cut it off, could not frighten him. Finally, he went away. Thus, even though they tested him again and again, they could not discover his weak point.

When he was ten years old, to test whether he was really deaf, they hung a curtain around a bed and made holes in the four sides. They placed conch blowers underneath it without letting him see them. All at once they blew the conchs. There was one, loud burst of sound. But the ministers, even though they stood at the four sides of the bed and watched through the holes in the curtain, could not detect any confusion in him throughout a whole day. They could not detect any disturbance of the hand or foot, or even a single startled reaction.

After a year had past, they tested him with drums. But even though they tested him again and again, they could not discover his weak point. Then they said, “We will test him with a lamp.” At night, to see whether he moved a hand or foot in the darkness, they lit some lamps in jars. They extinguished all the other lamps. Then suddenly lifting the lamps in the jars, they created a great blaze and watched his reaction. But though they tested him again and again for a whole year, they never saw him startled even once.

Then they said, “We will test him with molasses.” They smeared him all over with molasses. Then they put him in a place infested with flies and stirred the flies up. The flies covered his whole body and bit it as if they were piercing it with needles. But he remained motionless as if perfectly apathetic. Thus, they tested him for a year, but they discovered no weak point in him.

When he was 14 years old, they said, “Now that he is grown up, this youth loves what is clean and abhors what is unclean. We will test him with what is unclean.” So they did not let him bathe or rinse his mouth or perform any bodily cleaning until he was reduced to a miserable plight. He looked like a released prisoner. As he lay covered with flies, the people came round and reviled him. They said, “O Temiya, you are grown up now, who is to wait on you? Are you not ashamed? Why are you lying there? Rise up and clean yourself.” But remembering the torments of the hell Gūtha, he lay quietly in his squalor. And even though they tested him again and again for a year, they discovered no weak point in him.

Then they put pans of fire in the bed under him, saying, “When he is distressed by the heat, he will be unable to bear the pain and will show some signs of writhing.“ Boils broke out on his body, but the Bodhisatta resigned himself, saying, “The fire of the hell Avīci flames up a hundred leagues—this heat is a hundred, a thousand times preferable to that.” So he remained motionless.

Then his parents, with breaking hearts, made the men come back. They took him out of the fire and begged him, saying, “O prince Temiya, we know that you are not crippled by birth, for cripples do not have feet, a face, or ears like you. We received you as our child after many prayers. Do not destroy us now. Deliver us from the blame of all the kings of Jambudīpa.” (Jambudīpa is the four continents.) But even though they begged him, he lay motionless as if he had not heard them. His parents went away weeping.

Sometimes his father or his mother came back alone and implored him. They tested him again and again for a whole year, but they discovered no weak point in him. Then when he was 16 years old, they reflected, “Whether it be a cripple or someone who is deaf and dumb, still there are none who when they are grown up, do not delight in what is enjoyable and dislike what is disagreeable. This is natural in the proper time like the opening of flowers. We will have dramas acted before him, and in this way we will test him.”

So they summoned some women full of graces. They were as beautiful as the daughters of the gods. They promised that whichever of them could make the prince laugh or could entangle him in lustful thoughts would become his principal queen. They had the prince bathed in perfumed water and adorned like a son of the gods. They laid him on a royal bed prepared in a suite of royal chambers like the dwellings of the gods. They filled his inner chamber with a mingled fragrance of perfumed wreaths: wreaths of flowers, incense, unguents, spirituous liquor, and the like. Then they retired.

Meanwhile the women surrounded him and tried hard to delight him with dancing and singing and all sorts of pleasant words. But he looked at them in his perfect wisdom and stopped his breathing in fear that they should touch his body. His body became quite rigid. They were unable to touch him. They said to his parents, “His body is all rigid. He is not a man. He must be a goblin.” So his parents, even though they tested him again and again, discovered no weak point in him.

So even though they tested him for 16 years with the 16 great tests and many smaller ones, they were not able to detect a weak point in him. Then the exasperated king summoned the fortune tellers. He said, “When the prince was born you said that he has fortunate and auspicious marks. He has no threatening obstacle, but he is born a cripple and deaf and dumb. Your words do not answer to the facts.” “Great king,” they replied, “nothing is unseen by your teachers, but we knew how grieved you would be if we told you that the child of so many royal prayers would bring bad luck, so we did not say it.” “What must be done now?” “O king, if this prince remains in this house, three dangers are threatened: your life, your royal power, or the queen. Therefore, it will be best to have some unlucky horses yoked to an unlucky chariot. Place him in it. Then take him by the western gate and bury him in the charnel ground.” The king agreed, being frightened at the threatened dangers.

When the queen Candādevī heard the news, she went to the king. “My lord, you gave me a boon, and I have kept it unclaimed. Give it to me now.” “Take it, O queen.” “Give the kingdom to my son.” “I cannot, O queen. Your son is bad luck.” “Then if you will not give it for his lifetime, give it to him for seven years.” “I cannot, O queen.” “Then give it to him for six years—for five, four, three, two, one year. Give it to him for seven months, for six, five, four, three, two months, one month, for half a month.” “I cannot, O queen.” “Then give it to him for seven days.” “Well,” said the king, “take your boon.”

So she had her son adorned. The city was gaily decorated. A proclamation was made to the beat of a drum, “This is the reign of prince Temiya.” He was seated on an elephant and led triumphantly right wise around the city, with a white umbrella was held over his head. When he returned and was laid on his royal bed, she implored him all night. “O my child, prince Temiya, because of you I have cried and not slept for 16 years. My eyes are parched, and my heart is pierced with sorrow. I know that you are not a cripple or deaf and dumb. Do not make me utterly destitute.” In this manner she begged him day after day for five days.

On the sixth day the king summoned the charioteer Sunanda and said to him, “Tomorrow morning early, yoke some ill-omened horses to an ill-omened chariot. Put the prince in it. Then take him out by the western gate and dig a hole with four sides in the charnel ground. Throw him into it, break his head with the back of the spade, and kill him. Then scatter dust over him and make a heap of earth above. And after bathing yourself, come here.”

That sixth night the queen implored the prince, “O my child, the King of Kāsī has given orders that you are to be buried tomorrow in the charnel ground. Tomorrow you will certainly die, my son.” When the Bodhisatta heard this, he thought to himself, “O Temiya, your 16 years’ labor has reached its end,” and he was glad. But his mother’s heart was as if it were split in two. Still, he would not speak to her unless his desire should not attain its end. At the end of that night, in the early morning, Sunanda the charioteer yoked the chariot and stood it at the gate. He entered the royal bedchamber and said, “O queen, do not be angry, it is the king’s command.” As the queen lay embracing her son, he pushed her away with the back of his hand. He lifted the prince like a bundle of flowers and went down from the palace. The queen was left in the chamber beating her breast and lamenting with a loud cry. Then the Bodhisatta looked at her and thought, “If I do not speak, she will die of a broken heart.” But even though he wanted to speak, he reflected, “If I speak, my efforts for 16 years will have been fruitless. But if I do not speak, I will be the death of my father and mother as well as myself.”

The charioteer lifted him into the chariot and said, “I will drive the chariot to the gate.” He drove it to the eastern gate, and the wheel struck against the threshold. The Bodhisatta heard the sound and said, “My desire has attained its end.” He became still more glad at heart. When the chariot had left the city, it went three leagues by the power of the gods. And there at the edge of a forest there appeared to the charioteer what looked like a charnel ground. So thinking it was a suitable place, he turned the chariot off the road. He stopped by the roadside, dismounted, and took off all the Bodhisatta’s ornaments. He made them into a bundle and laid them down. Then he took a spade and began to dig a hole.

Then the Bodhisatta thought, “This is my time for effort. For 16 years I have never moved my hands or my feet. Are they in my power or not?” So he rose and rubbed his right hand with his left and his left hand with his right. He rubbed his feet with both his hands, and he resolved to descend from the chariot. When his foot came down, the earth rose up like a leather bag filled with air and touched the back end of the chariot. When he had descended and had walked backwards and forwards several times, he felt that he had the strength to go a hundred leagues in this manner in one day. Then he reflected, “If the charioteer were to turn against me, will I have the power to contend with him?” So he seized hold of the back end of the chariot and lifted it up as if it were a toy cart for children. He told himself that he had the power to contend with him.

Then he had the desire to adorn himself. At that moment Sakka’s palace became hot. Sakka, having perceived the reason, said, “Prince Temiya’s desire has attained its end. He wants to be adorned. What has he to do with human adornment?” He commanded Vissakamma (the chief architect of the heavenly realms) to take heavenly decorations and to go and adorn the son of the King of Kāsī. He went and wrapped the prince with 10,000 pieces of cloth and adorned him like Sakka with heavenly and human ornaments. The prince, decked with all the bravery of the King of the gods, went up to the hole as the charioteer was digging. He stood at the edge and uttered the third stanza:

“Why in such haste, O charioteer? And wherefore do you dig that pit?

Answer my question truthfully. What do you want to do with it?”

The charioteer went on digging the hole without looking up and spoke the fourth stanza:

“Our king has found his only son crippled and dumb, an idiot quite,

And I am sent to dig this hole and bury him far out of sight.”

The Bodhisatta replied:

“I am not deaf or dumb, my friend, no cripple, not e’en lame am I,

If in this wood you bury me, you will incur great guilt thereby.

“Behold these arms and legs of mine, and hear my voice and what I say,

If in this wood you bury me, you will incur great guilt today.”

Then the charioteer said, “Who is this? It is only since I came here that he has become as he describes himself.” So he stopped digging the hole and looked up. He beheld his glorious beauty, and not knowing whether he was a god or a man, he spoke this stanza:

“A heavenly minstrel or a god, or are you Sakka, lord of all?

Who are you, pray, whose son are you? What shall we name you when we call?”

Then the Bodhisatta spoke revealed himself and declaring the Dharma:

“No heavenly minstrel nor a god, nor Sakka, lord of all, am I,

I am the King of Kāsi’s son whom you would bury ruthlessly.

“I am the son of that same king under whose sway you serve and thrive,

You will incur great guilt today if here you bury me alive.

“If ‘neath a tree I sit and rest while it its shade and shelter lends,

I would not break a single branch, only the wicked harms his friends.

“The sheltering tree—it is the king—I am the branch that tree has spread,

And you the traveler, charioteer, who sits and rests beneath its shade,

If in this wood you bury me, great guilt will fall upon your head.”

But even though the Bodhisatta said this, the man did not believe him. Then the Bodhisatta resolved to convince him. He made the woods resound with his own voice and the applause of the gods as he spoke these ten verses in honor of friends:

“He who is faithful to his friends may wander far and wide,

Many will gladly wait on him, his food shall be supplied.

“Whatever lands he wanders through, in city or in town,

He who is faithful to his friends finds honor and renown.

“No robbers dare to injure him, no warriors him despise,

He who is faithful to his friends escapes all enemies.

“Welcomed by all he home returns, no cares corrode his breast,

He who is faithful to his friends is of all kin the best.

“He honors and is honored too, respect he takes and gives,

He who is faithful to his friends, honor from all receives.

“He is by others honored who to them due honor pays,

He who is faithful to his friends wins himself fame and praise.

“Like fire he blazes brightly forth, and sheds a light divine,

He who is faithful to his friends will with fresh splendor shine.

“His oxen surely multiply, his seed unfailing grows,

He who is faithful to his friends reaps surely all he sows.

“If from a mountain top he falls or from a tree or slot,

He who is faithful to his friends finds a sure resting spot.

“The banyan tree defies the wind, girt with its branches rooted round,

He who is faithful to his friends does all the rage of foes confound.”

But despite this discourse, Sunanda did not recognize him and asked who he was. But as he approached the chariot, even before he saw the chariot and the ornaments that the prince wore, he recognized him. He fell at his feet, and folding his hands, he spoke this stanza:

“Come, I will take you back, O prince, to your own proper home,

Sit on the throne and be the king, why in this forest roam?”

The Great Being replied:

“I do not want the throne or wealth, I want not friends or kin,

Since ‘tis by evil acts alone that I that throne could win.”

The charioteer spoke:

“A brimful cup of welcome, prince, will be prepared for thee,

And your two parents in their joy great gifts will give to me.

“The royal wives, the princes all, Vesiyas and brahmans both,

Great presents in their full content will give me, nothing loth.

(Vesiyas are courtesans.)

“Those who ride elephants and cars, foot soldiers, royal guards,

When you do return home again, will give me sure rewards.

“The country folk and city folk will gather joyously,

And when they see their prince returned will presents give to me.”

The Great Being spoke:

“By parents I was left forlorn, by city and by town,

The princes left me to my fate; I have no home my own.

“My mother gave me leave to go, my father me forsook,

Here in this forest, wild alone, the ascetic’s vow I took.”

As the Great Being called to mind his virtues, delight arose in his mind, and in his ecstasy he uttered a hymn of triumph:

“Even to those who hurry not, the heart’s longing wins success,

Know, charioteer, that I today have gained ripe holiness.

“Even by those who hurry not, the highest end is won,

Crowned with ripe holiness I go, perfect and fearing none.”

The charioteer replied:

“Your words, my lord, are pleasant words, open your speech and clear,

Why were you dumb, when you did see father and mother near?”

The Great Being spoke:

“No cripple I for lack of joints, nor deaf for lack of ears,

I am not dumb for want of tongue as plainly now appears.

“In an old birth I played the king, as I remember well,

But when I fell from that estate, I found myself in hell.

“Some twenty years of luxury I passed upon that throne,

But eighty thousand years in hell did for that guilt atone.

“My former taste of royalty filled all my heart with fear,

Then I was dumb, although I saw father and mother near.

“My father took me on his lap, but midst his fondling play,

I heard the stern commands he gave, ‘At once this miscreant slay,

Split him in pieces, go, that wretch impale without delay.’

“Hearing such threats well might I try crippled and dumb to be,

And wallow helplessly in filth, an idiot willingly.

“Knowing that life is short at best and filled with miseries,

Who ‘gainst another for its sake would let his anger rise?

“Who on another for its sake would let his vengeance light,

Through want of power to grasp the truth and blindness to the right?”

Then Sunanda reflected, “This prince, abandoning all his royal pomp as if it were carrion, has entered the wood, unwavering in his resolve to become an ascetic. What have I to do with this miserable life? I, too, will become an ascetic with him.” So he spoke this stanza:

“I, too, would choose the ascetic’s life with thee,

Call me, O prince, for I as you would be.”

When he made this request, the Great Being reflected, “If I admit him to the ascetic life now, my father and mother will not come here and they will suffer a great loss. The horses and chariot and ornaments will perish. Blame will come to me. Men will say, “He is a goblin. Has he devoured the charioteer?” So wishing to save himself from blame and to provide for his parents’ welfare, he entrusted the horses and chariot and ornaments to him and spoke this stanza:

“Restore the chariot first, you are not a free man now.

First pay your debts, they say, then take the ascetic’s vow.”

The charioteer thought to himself, “If I go to the city and he leaves, his father and mother will come back with me to see him. But if they do not find him they will punish me. I will explain the circumstances in which I find myself and make him promise to remain here.” So he spoke two stanzas:

“Since I have done your bidding, prince, I pray,

Do you be pleased to do what I shall say.

“Stay till I fetch the king, stay here of grace,

He will be joyful when he sees your face.”

The Great Being replied:

“Well, be it as you do say, charioteer,

I, too, would gladly see my father here.

“Go and salute my kindred all, and take

A special message for my parents’ sake.”

The man took the commands:

He clasped his feet and, all due honors paid,

Started to journey as his Master bade.

At that moment Candādevī opened her window. She wondered if there were any word of her son. She looked down the road by which the charioteer would return, and when she saw him coming alone, she burst into tears.

The Master described it in this way:

“Seeing the empty car and lonely charioteer,

The mother’s eyes were filled with tears, her breast with fear.

“’The charioteer comes back, my son is slain,

Yonder he lies, earth mixed with earth again.

“’Our bitterest foes may well rejoice, alack!

Seeing his murderer come safely back.

“’Dumb, crippled, say, could he not give one cry,

As on the ground he struggled helplessly?

“’Could not his hands and feet force you away,

Though dumb and maimed, while on the ground he lay?’”

The charioteer spoke:

“Promise me pardon, lady, for my word,

And I will tell you all I saw and heard.”

The queen answered:

“Pardon I promise you for every word,

Tell me in full whate’er you saw or heard.”

Then the charioteer spoke:

“No cripple he, he is not deaf, his utterance clear and free,

He played fictitious parts at home, through dread of royalty.

“In an old birth he played the king as he remembers well,

But when he fell from that estate, he found himself in hell.

“Some twenty years of luxury he passed upon that throne,

But eighty thousand years in hell did for that guilt atone.

“His former taste of royalty filled all his heart with fear,

Hence, he was dumb although he saw father and mother near.

“Perfectly sound in all his limbs, faultlessly tall and broad,

His utterance clear, his wits undimmed, he treads salvation’s road.

“If you desire to see your son, then come at once with me,

You shall behold prince Temiya, perfectly calm and free.”

But when the prince had sent the charioteer away, he wanted to take the ascetic vow. Knowing his desire, Sakka sent Vissakamma, saying, “Prince Temiya wishes to take the ascetic vow. Go and make a hut of leaves for him and give him the requisite articles for an ascetic.” He hastened accordingly, and in a grove of trees three leagues in extent he built a hermitage. It was furnished with an apartment for the night and another for the day. He built a tank and a pit. He planted fruit trees, and he prepared all the requisites for an ascetic. Then he returned to his own place.

When the Bodhisatta saw it, he knew that it was Sakka’s gift. He entered the hut, took off his clothes, and put on the red bark garments. He threw the black antelope skin on one shoulder and tied up his matted hair. Then, having taken a carrying pole on his shoulder and a walking staff in his hand, he went out of the hut. He walked repeatedly up and down, displaying the full dress of an ascetic. He shouted triumphantly, “O the bliss, O the bliss.” (This is reminiscent of the Bhaddiya Sutta, Ud 2.10.) Then he returned to the hut and sat down on the ragged mat. He entered the five transcendent faculties (faith, energy, mindfulness, concentration, and wisdom). Then he went out in the evening. He gathered some leaves from a kāra tree. He soaked them in a vessel supplied by Sakka in water without salt or buttermilk or spice. He ate them as if they were ambrosia, and then, as he attained the four perfect states (jhānas), he resolved to take up his residence there.

Meanwhile the King of Kāsī, having heard Sunanda’s words, summoned his chief general and ordered him to prepare for the journey:

“The horses to the chariots yoke, bind girths on elephants and come,

Sound conch and tabour far and wide and wake the loud-voiced kettledrum.

“Let the hoarse tom-tom fill the air, let rattling drums raise echoes sweet,

Bid all this city follow me, I go my son once more to greet.

“Let palace ladies, every prince, vesiyas and brahmans every one,

All have their chariot horses yoked, I go to welcome back my son.

“Let elephant riders, royal guards, horsemen and footmen every one,

“Let all alike prepare to go, I go to welcome back my son.

“Let country folk and city folk gather in crowds in every street,

Let all alike prepare to go, I go once more my son to greet.”

Having been so ordered, the charioteers yoked the horses. They brought the chariots to the palace gates, and then they informed the king.

The Master has thus described it:

“Sindh horses of the noblest breed stood harnessed at the palace gates,

The charioteers the tidings bring, ‘The train, my lord, your presence waits.’”

The king spoke:

“Leave all the clumsy horses out, no weaklings in our cavalcade,”

(They told the charioteer, “Be sure not to bring horses of that kind,”)

Such were the royal orders given, and such the charioteers obeyed.

The king prepared to see his son. He assembled the four castes, the 18 guilds, and his whole army. (Technically there was no caste system at the time of the Buddha. Rather they had a “pre-caste” system called the “varna” system that included these four groups.) They spent three days assembling the host. On the fourth day, having taken all that was to be taken in the procession, he proceeded to the hermitage. There he was greeted by his son, and the king gave him due greeting in return.

The Master described it in this way:

“His royal chariot then prepared, the king without delay

Got in and cried out to his wives, ‘Come with me all away!’

“With yak’s tail fan and turban crest, and royal white sunshade,

He mounted in the royal car with finest gold arrayed.

“Then did the king set forth at once, his charioteer beside,

And quickly went where Temiya all tranquil did abide.

“When Temiya then saw him come all brilliant and ablaze,

Surrounded by attendant bands of warriors, thus he says:

“‘Father, I hope ‘tis well with you, you have good news to tell,

I hope that all the royal queens, my mothers, too, are well?’

“‘Yes, it is well with me, my son, I have good news to tell,

And all the royal queens indeed, your mothers, all are well.’

“’I hope you do not strong drink, and spirits you do eschew,

To righteous deeds and almsgiving your mind is ever true?’

“’Oh yes, strong drink I never touch, all spirit I eschew,

To righteous deeds and almsgiving my mind is ever true.’

“’The horses and the elephants I hope are well and strong,

No painful bodily disease, no weakness, nothing wrong?’

“’Oh yes, the elephants are well, the horses well and strong,

No painful bodily disease, no weakness, nothing wrong.’

“’The frontiers, as the central part, all populous, at peace,

The treasures and the treasuries quite full—say, what of these?

“’Now welcome to you, royal Sir, O welcome now to thee!

Let them set out a couch, that here seated the king may be.’”

The king, out of respect for the Great Being, would not sit upon the couch.

The Great Being said, “If he does not sit on his royal seat, let a couch of leaves be spread for him,” so he spoke a stanza:

“Be seated on this bed of leaves spread for you as is meet,

They will take water from this spot and duly wash your feet.”

Out of respect, the king would not accept even the seat of leaves, but he sat on the ground. Then the Bodhisatta entered the hut of leaves. He took out a kāra leaf, and inviting the king, he spoke a stanza:

“No salt have I, this leaf alone is what I live upon, O king,

You have come here a guest of mine, be pleased to accept the fare I bring.”

The king replied:

“No leaves for me, that’s not my fare. Give me a bowl of pure hill rice,

Cooked with a subtle flavoring of meat to make the pottage nice.”

At that moment the queen Candādevī, surrounded by the royal ladies, arrived. And after clasping her dear son’s feet and saluting him, she sat on one side with her eyes full of tears. The king said to her, “Lady, see what your son’s food is.” He put some of the leaves into her hand and also gave some to the other ladies. They took it, saying, “O my lord, do you indeed eat such food? You endure great hardship.” Then they sat down. The king said, “O my son, this appears wonderful to me,” and he spoke a stanza:

“Most strange indeed it seems to me that you thus left alone

Do live on such mean food and yet your color is not gone.”

The prince replied:

“Upon this bed of leaves strewn here I lie indeed alone,

A pleasant bed it is and so my color is not gone.

“Girt with their swords no cruel guards stand sternly looking on,

A pleasant bed it is and so my color is not gone.

“Over the past I do not mourn nor for the future weep,

I meet the present as it comes, and so my color keep.

“Mourning about the hopeless past or some uncertain future need,

This dries a young man’s vigor up as when you cut a fresh green reed.”

The king thought to himself, “I will declare him as king and take him away with me.” He spoke these stanzas inviting him to share the kingdom:

“My elephants, my chariots, horsemen, and infantry,

And all my pleasant palaces, dear son, I give to thee.

“My queen’s apartments, too, I give, with all their pomp and pride,

You shall be sole king over us, there shall be none beside.

“Fair women skilled in dance and song and trained for every mood

Shall lap your soul in ease and joy, why linger in this wood?

“The daughters of your foes shall come proud but to wait on thee,

When they have borne you sons, then go a recluse so to be.

“Come, O my first born and my heir, in the first glory of your age,

Enjoy your kingdom to the full, what do you in this hermitage?”

The Bodhisatta spoke:

“No, let the young man leave the world and flee its vanities,

The ascetic’s life best suits the young, so counsel all the wise.

“No, let the young man leave the world, a hermit and alone,

I will embrace the hermit’s life. I need no pomp nor throne.

“I watch the boy, with childish lips he ‘father’ ‘mother,’ cries,

Himself begets a son, and then he, too, grows old and dies.

“So the young daughter in her flower grows blithe and fair to see,

But she soon fades cut down by death like the green bamboo tree.

“Men, women all, however young, soon perish, who in truth

Would put his trust in mortal life, cheated by fancied youth?

“As night by night gives place to dawn life still contracts its span,

Like fish in water which dries up, what means the youth of man?

“This world of ours is smitten sore, is ever watched by one,

They pass and pass with purpose fell, why talk of crown or throne?

“Who sorely smites this world of ours? who watches grimly by?

And who thus pass with purpose fell? Tell me the mystery.

“‘Tis death that smites this world, old age who watches at our gate,

And ‘tis the nights which pass and win their purpose soon or late.

“As when the lady at her loom sits weaving all the day,

Her task grows ever less and less, so waste our lives away.

“As speeds the hurrying river’s course, on with no backward flow,

So in its course the life of men does ever forward go.

“And as the river sweeps away trees from its banks uptorn,

So are we men by age and death in headlong ruin born.”

As he listened to the Great Being’s discourse, the king became disgusted at a life spent in a house. He longed to leave the world. He exclaimed, “I will not go back to the city. I will become an ascetic here. If my son will go to the city, I will give him the white umbrella.” So to test him, he invited him once more to take his kingdom:

“My elephants, my chariots, horsemen, and infantry,

And all my pleasant palaces, dear son, I give to thee.

“My queen’s apartments, too, I give, with all their pomp and pride,

You shall be sole king over us, there shall be none beside.

“Fair women skilled in dance and song and trained for every mood

Shall lap your soul in ease and joy, why linger in this wood?

“The daughters of your foes shall come proud but to wait on thee,

When they have borne you sons, then go a recluse so to be.

“My treasures and my treasuries, footmen and cavalry,

And all my pleasant palaces, dear son, I give to thee.

“With troops of slaves to wait on thee, and queens to be embraced,

Enjoy your throne, all health to you, why linger in this waste?”

But the Great Being replied by showing how little he wanted a kingdom.

“Why seek for wealth, it will not last, why woo a wife, she soon will die,

Why think of youth, ‘twill soon be past, and threatening age stands ever nigh.

“What are the joys that life can bring? beauty, sport, wealth, or royal fare?

What is a wife or child to me? I am set free from every snare.

“This thing I know, where’er I go, Fate—watching—never loses breath,

Of what avail is wealth or joy to one who feels the grasp of death?

“Do what you have to do today, who can ensure tomorrow’s sun?

Death is the Master general who gives his guarantee to none.

“Thieves ever watch to steal our wealth, I am set free from every chain,

Go back and take your crown away, I do not want a king’s domain?”

The Great Being’s discourse ended.

And when they heard it, not only the king and the queen Candā but the 16,000 royal wives all wanted to embrace the ascetic life. The king ordered a proclamation to be made in the city by beat of the drum that all who wished to become ascetics with his son should do so. He caused the doors of his treasuries to be thrown open. He had an inscription written on a golden plate and fixed on a great bamboo as a pillar. It said that his treasure jars would be opened and that all who pleased might take of them. The citizens also left their houses with the doors open as if it were an open market. They flocked around the king. The king and the multitude took the ascetic vow together before the Great Being. Sakka erected a hermitage that extended for three leagues. The Great Being went through the huts made of branches and leaves, and he appointed those in the center for the women while those on the outside were for the men.

On the fast day they stood on the ground and gathered and ate the fruits of the trees that Vissakamma had created. They followed the rules of the ascetic life. The Great Being knew the minds of everyone, whether they indulged thoughts of lust or malevolence or cruelty. He sat in the air and taught the Dharma to all. As they listened, they quickly developed the Faculties (desire, intention, energy, and investigation) and the Attainments (jhānas).

A neighboring king heard that Kāsirājā had become an ascetic. He resolved to rule in Benares. So he entered the city, and seeing it all decorated, he went up into the palace. He saw the seven kinds of precious stones (gold, silver, pearl, coral, cat’s-eye, ruby, and diamond) there. He thought that some kind of danger must surround all this wealth. So he sent for some drunken revelers and asked them by which gate the king had left. They told him, “By the eastern gate.” So he went out by that gate and proceeded along the bank of the river.

The Great Being knew he was coming. He went out to meet him. He sat in the air and taught the Dharma. Then the invader took the ascetic vow with all his company. The same thing also happened to another king. In this way three kingdoms were abandoned. The elephants and horses were left to roam wild in the woods. The chariots dropped to pieces in the woods. The money in the treasuries was treated as mere sand. It was scattered about in the hermitage. All the residents attained to the eight Ecstatic Meditations (jhānas). And at the end of their lives, they became destined for the world of Brahma. Even the animals—the elephants and horses—had their minds calmed by the sight of the sages and were reborn in the six heavens of the gods.

The Master, having brought his lesson to an end, said, “Not only now but in the past I also left a kingdom and become an ascetic.” Then he identified the birth: “the goddess in the umbrella was Uppalavaṇṇā, the charioteer was Sāriputta, the father and mother were the royal family, the court was the Buddha’s Saṇgha, and I was the wise Mūgapakkha.”

(Uppalavaṇṇā was one of the Buddha’s chief bhikkhunis.)

After they went to the island of Ceylon (Sri Lanka), Elder Khuddakatissa, a native of Maṅgaṇa, Elder Mahāvaṁsaka, Elder Phussadeva, who lived at Kaṭakandhakāra, Elder Mahārakkhita, a native of Uparimaṇḍakamāla, Elder Mahātissa, a native of Bhaggari, Elder Mahāsiva, a native of Vāmattapabbhāra, Elder Mahāmaliyadeva, a native of Kāḷavela are called the late comers in the assembly of the Kuddālaka birth (Jātaka 70), the Mūgapakkha birth (Jātaka 538), the Ayoghara birth (Jātaka 510), and the Hatthipāla birth (Jātaka 509). Moreover, Elder Mahānāga, a native of Maddha, and Elder Maliyamakādeva, remarked on the day of Pārīnibbāna, “Sir, the assembly of the Mūgapakkha birth is today extinct.” “Wherefore?” “I was then passionately addicted to spirituous drink, and when I could not bring those with me who used to drink liquor with me, I was the last of all to give up the world and become an ascetic.”