Jataka 539

Mahājanaka Jātaka

King Mahājanaka

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by H.T. Francis and R.A. Neil, Cambridge University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

This is another story where a rich and powerful king renounces worldly life to become an ascetic, a renunciate. This runs counter to just about every other culture in the world. We value education, “success,” power, wealth, status, and position. But in these stories, the true glory comes from utter simplicity. It comes from living peacefully. It comes from non-harming. It comes from virtue and integrity. Material wealth usually equates to spiritual poverty and vice versa. The true wealth is spiritual wealth, and that comes from deep, profound goodness.

“Who are you, striving?” The Master told this story while he was living at Jetavana. It is about the Great Renunciation. One day the monks sat in the Dharma Hall discussing the Tathāgata’s great Renunciation. The Master came and discovered that this was their subject. He said, “This is not the first time that the Tathāgata performed the great Renunciation. He performed it in the past as well.” Then he told them this story from the past.

Once upon a time there was a king named Mahājanaka reigning in Mithilā in the kingdom of Videha. He had two sons, Ariṭṭhajanaka and Polajanaka. He made the elder son viceroy and the younger son commander-in-chief. Afterwards, when Mahājanaka died, Ariṭṭhajanaka become king, and he gave the viceroyalty to his brother.

One day a slave went to the king and told him that the viceroy wanted to kill him. The king repeatedly had already heard the same story. He became suspicious. He had Polajanaka thrown into chains, and he imprisoned him with a guard in a house not far from the palace. The prince made a solemn declaration: “If I am my brother’s enemy, let not my chains be unloosed nor the door become opened. But otherwise, may my chains be unloosed and the door become opened.” Thereupon the chains broke into pieces and the door flew open.

He left and went to a frontier village where he took up residence. The inhabitants recognized him. They waited on him, and the king was unable to have him arrested. In course of time, he became master of the frontier district, and now—having a large following—he said to himself, “If I was not my brother’s enemy before, I am indeed his enemy now.”

He went to Mithilā with a large host and camped on the outskirts of the city. The inhabitants heard that Prince Polajanaka had come. Most of them joined him with their elephants and other riding animals, and the inhabitants of other towns also gathered with them. So he sent a message to his brother, “I was not your enemy before, but I am indeed your enemy now. Give the royal umbrella up to me or give battle.”

(The royal umbrella is the official symbol of power.)

As the king went to give battle, he bade farewell to his principal queen. “Lady,” he said, “victory and defeat in a battle cannot be foretold. If any fatal accident comes to me, carefully preserve the child in your womb.” So saying, he departed.

The soldiers of Polajanaka took his life in battle. The news of the king’s death caused universal confusion in the whole city. The queen, having learned that he was dead, quickly put her gold and choicest treasures into a basket. She spread a cloth on the top and strewed some husked rice over that. And having put on some soiled clothes and disguised herself, she set the basket on her head and went out at an unusual time of the day. No one recognized her.

She went out by the northern gate, but she did not know the way. She had never gone anywhere before and was unable to determine the correct direction. She had heard that there was such called Kāḷacampā. She sat down and started asking whether there were any people going to Kāḷacampā city.

Now it was no common child in her womb. It was the Great Being reborn. He had accomplished the Perfections, and all Sakka’s world shook with his majesty. Sakka considered what the cause could be. He reflected that a being of great merit must have been conceived in her womb and that he must go and see it. So he created a covered carriage and prepared a bed in it. Then he stood at the door of the house where she was sitting as if he were an old man driving the carriage. He asked if anyone wanted to go to Kāḷacampā. “I want to go there, father.” “Then mount up into this carriage, lady, and take your seat.” “Father, I am far gone with child, and I cannot climb up. I will follow behind but give me room for my basket.” “What are you talking about, mother? There is no one who knows how to drive a carriage like me. Fear not. Climb up and sit down.”

Using his divine power, he caused the earth to rise as she was climbing up and made it touch the rear end of the carriage. She climbed up and lay down in the bed. She realized that he must be a god.

As soon as she lay down on the divine bed, she fell asleep. After going thirty leagues (a league is three miles or 4.828 kilometers), Sakka came to a river. He woke her and said, “Mother, get down and bathe in the river. At the head of the bed there is a cloak. Put it on, and in the carriage, there is a cake for you to eat.” She did so and lay down again. In the evening, they reached Campā. She saw the gate, the watchtower, and the walls. She asked what city it was. He replied, “Campā city, mother.” “What do you say, father? Is it not 60 leagues from our city to Campā?” “It is so, mother, but I know the straight road.” He then made her disembark at the southern gate. “Mother, my village lies further on, but you should enter the city.” And so saying, Sakka went on. Then he vanished, and he returned to his own realm.

The queen sat down in a certain hall. At that time there was a brahmin. He was a reciter of hymns who lived in Campā. He was going with his 500 disciples to bathe. He saw her sitting there so fair and attractive. He used his power to see the being in her womb. He developed an affection for her as if she were a youngest sister. He had his pupils stay outside while he went alone into the hall. He asked her, “Sister, in what village do you live?” “I am the chief queen of King Ariṭṭhajanaka in Mithilā,” she replied. “Why are you here?” “The king has been killed by Polajanaka, and I have come here in fear to save my unborn child.” “Do you have any family in this city?” “There are none, father.” “Do not be anxious. I am a Northern Brahmin of a great family, a teacher famed far and wide. I will watch over you as if you were my sister. Call me your brother, clasp my feet, and make a loud lamentation.”

She made a great wailing and fell at his feet, and they each expressed sympathy with the other. His pupils came running up and asked him what it all meant. “This is my youngest sister. She was born at a time when I was away.” “O teacher, do not grieve now that you have seen her at last.” He caused a grand covered carriage to be brought. He had her sit down in it and sent her to his house. He had them tell his wife that it was his sister and that his wife was to do everything that was necessary. His brahmin wife gave her a hot water bath, prepared a bed for her, and had her lie down.

The brahmin bathed and then he went home. At the mealtime he had them call his sister, and he ate with her. He watched over her in the house. Soon after she brought forth a son. They named him Prince Mahājanaka after his grandfather.

He grew up and played with the local boys. They used to provoke him with their own pure Khattiya (class) birth, but he would strike them roughly with his own superior strength and stoutness of heart. When they cried and were asked who had struck them, they would reply “The widow’s son.” The prince reflected “They always call me the widow’s son. I will ask my mother about it.” So one day he asked her, “Mother, whose son am I?” She deceived him, saying that the brahmin was his father. When he beat them another day and they called him the widow’s son, he replied that the brahmin was his father. They retorted, “What is the brahmin to you?” He reflected, “These lads say, “What is the brahmin to you?” My mother will not explain the matter to me. She will not tell me the truth for her own honor’s sake. I will make her tell it to me.”

So when he was sucking her milk, he bit her breast and said to her, “Tell me who my father is. If you do not tell me, I will cut your breast off.” So, unable to deceive him, she said, “My child, you are the son of King Ariṭṭhajanaka of Mithilā. Your father was killed by Polajanaka, and I came to this city to save you. The brahmin has treated me as his sister and taken care of me.” From that time on he was no longer angry when he was called the widow’s son.

Before he turned 16 years old, he had learned the three Vedas and all the sciences. And by the time he was 16, he had become very handsome. He thought to himself, “I will seize the kingdom that belonged to my father.” So he asked his mother, “Have you any money? If not, I will carry on a trade and make enough money to seize my father’s kingdom.” “Son, I did not come empty-handed. I have a store of pearls and jewels and diamonds sufficient for gaining the kingdom. Take them and seize the throne. You do not have to practice a trade.” “Mother,” he said, “give that wealth to me, but I will only take half of it. Then I will go to Suvaṇṇabhūmi and get great riches there. Then I will seize the kingdom.”

He made her bring him half the treasure, and having mastered his stock-in-trade, he put the riches on board a ship with some merchants bound for Suvaṇṇabhūmi. He bade his mother farewell, telling her that he was sailing for that country. “My son,” she said, “the sea has few chances of success and many dangers. Do not go. You have enough money to seize the kingdom.” But he told his mother that he would go. He bade her good-bye and embarked on board.

On that very day a disease broke out in Polajanaka, and he could not rise from his bed. There were seven caravans with their animals on board. It took the ship seven days to travel 700 leagues. But the trip was rough. The ship could not hold out. Its planks gave way, and the water rose higher and higher. The ship began to sink in the middle of the ocean. The crew wept and lamented and invoked their different gods. But the Great Being never wept or lamented or invoked any deities. But knowing that the vessel was doomed, he rubbed some sugar and ghee on himself. And, having eaten his fill, he smeared his two clean garments with oil. He put them tightly around him and stood leaning against the mast.

When the vessel sank the mast stood upright. The crowd on board became food for the fish and tortoises. The water all around assumed the color of blood. But the Great Being, standing on the mast, knew the direction in which Mithilā lay. He flew up from the top of the mast, and using his strength, he passed beyond the fish and tortoises and fell at the distance of 140 cubits from the ship. (A cubit is about 18 inches.) And on that very day, Polajanaka died.

After that the Great Being crossed through the jewel-colored waves. He made his way like a mass of gold. A week passed as if it had been a day, and when he saw the shore again, he washed his mouth with salt water and kept the fast.

Now at that time a daughter of the gods named Maṇimekhalā had been appointed guardian of the sea by the four guardians of the world. They said to her, “Those beings who possess such virtues as reverence for their mothers and the like do not deserve to fall into the sea. Look out for them.” But for those seven days she had not looked at the sea, for they say that her memory had become clouded in her enjoyment of divine happiness. Others say that she had gone to be present at a divine assembly. At last, however, she did look. She said to herself, “This is the seventh day that I have not looked at the sea. Who is making his way there?” As she saw the Great Being she thought to herself, “If Prince Mahājanaka had perished in the sea, I should not have attended the divine assembly!” So assuming an adorned form, she stood in the air not far from the Bodhisatta and uttered the first stanza:

“Who are you, striving manfully here in mid-ocean far from land?

Who is the friend you most trust in, to lend to you a helping hand?”

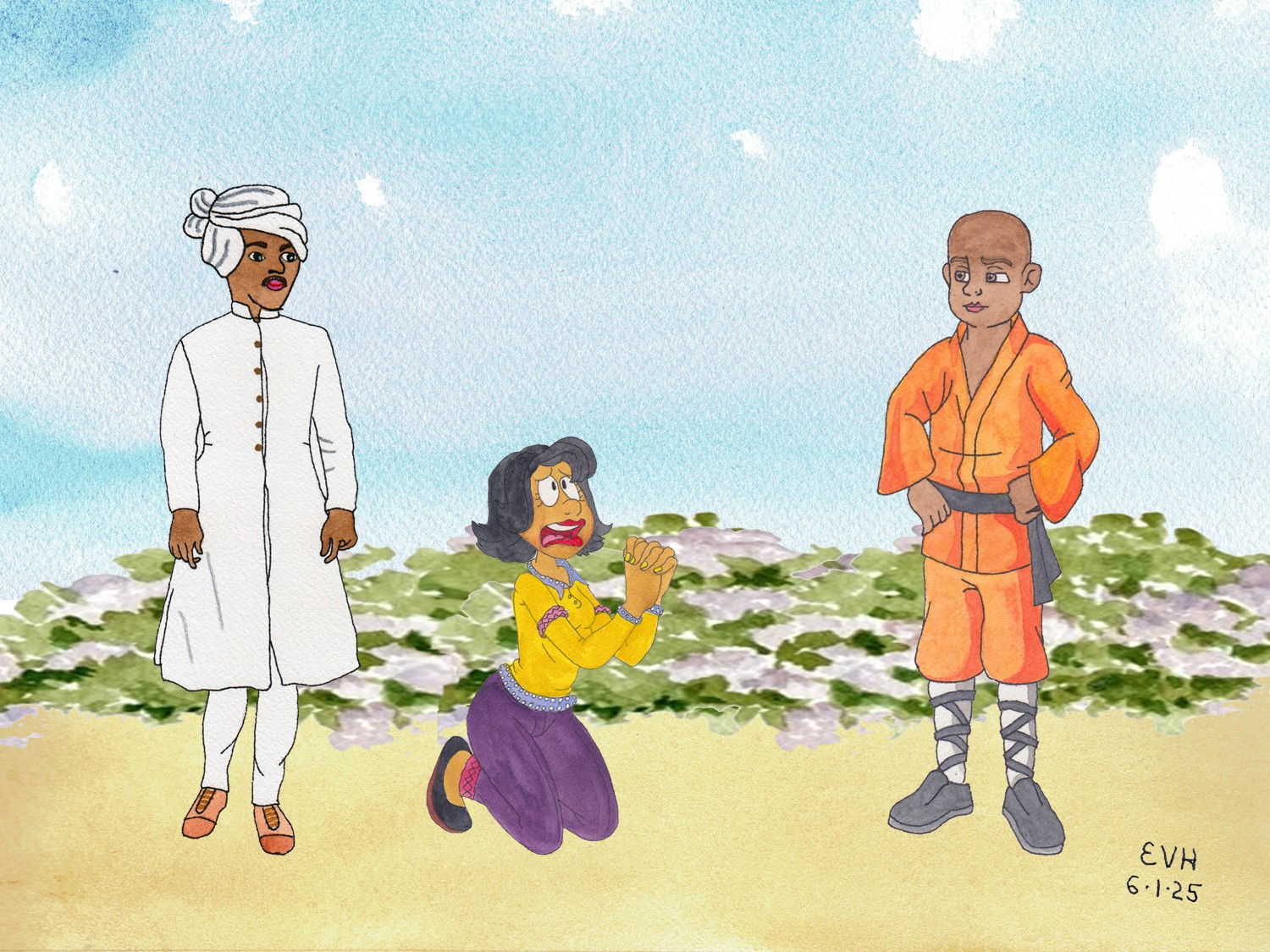

Figure: “Who are you striving far from land?”

The Bodhisatta replied, “This is my seventh day here in the ocean. I have not seen another living being beside myself. Who can it be that speaks to me?” So he looked into the air and uttered the second stanza:

“Knowing my duty in the world, to strive, O goddess, while I can,

Here in mid-ocean far from land I do my utmost like a man.”

Desiring to hear sound doctrine, she uttered to him the third stanza:

“Here in this deep and boundless waste where shore is none to meet the eye,

Your utmost strivings are in vain. Here in mid-ocean you must die.”

The Bodhisatta replied, “Why do you say this? If I perish while I make my best efforts, I shall in any event escape blame.” And he spoke a stanza:

“He who does all a man can do is free from guilt towards his kin,

The lord of heaven acquits him, too, and he feels no remorse within.”

Then the goddess spoke a stanza:

“What use in strivings such as these, where barren toil is all the gain,

Where there is no reward to win, and only death for all your pain?”

Then the Bodhisatta uttered these stanzas to show her lack of wisdom:

“He who thinks there is nought to win and will not battle while he may,

But has the blame whate’er the loss, ’twas his faint heart that lost the day.

“Men in this world devise their plans and do their business as seems best,

The plans may prosper or may fail, the unknown future shows the rest.

“You see not, goddess, here today ‘tis our own actions which decide,

Drowned are the others, I am saved, and you are standing by my side.

So I will ever do my best to fight through ocean to the shore,

While strength holds out, I still will strive, nor yield till I can strive no more.”

The goddess, on hearing his stout words, uttered a stanza of praise:

“You who so bravely do fight on amidst this fierce unbounded sea

Do not shrink from the appointed task, striving where duty does call thee,

Go where your heart would have you go, nor let nor hindrance shall there be.”

Then she asked him where she should take him. He answered, “to the city of Mithilā.” She grabbed him like a garland, and seizing him in both arms and making him lie on her bosom, she took him as if he was her dear child and sprang up in the air. For seven days the Bodhisatta slept, his body wet with the salt spray and thrilled with the heavenly contact. Then she brought him to Mithilā and laid him on his right side on the ceremonial stone in a mango grove. And, leaving him in the care of the goddesses of the garden, she departed to her own realm.

Now Polajanaka had no son. He had left only one daughter named Sīvalīdevī. She was wise and learned. They had asked him on his death bed, “O king, to whom shall we give the kingdom when you have become a god?” He replied, “Give it to him who can please the princess, my daughter Sīvalī, or to one who knows which is the head of the square bed, or who can string the bow that requires the strength of a thousand men, or who can draw out the 16 great treasures.” “O king, tell us the list of the treasures.” Then the king repeated it:

“The treasure of the rising sun, the treasure at his setting seen,

The treasure outside, that within, and that not outside nor within,

“At the mounting, at the dismounting, sāl-pillars four, the yojana round,

The end of the teeth, the end of the tail, the kebuka, the ends of the trees,

“The sixteen precious treasures these, and these remain, where these are found,

The bow that tasks a thousand men, the bed, the lady’s heart to please.”

(A “yojana” is a yoke. The “kebuka” is a river.)

The king, besides these treasures, also repeated a list of others. After his death, the ministers performed his funeral rites, and on the seventh day they assembled and deliberated. “The king said that we were to give the kingdom to him who is able to please his daughter, but who will be able to please her?” They said, “The general is a favorite.” So they sent for him. He came at once to the royal gate and signified to the princess that he was there. She knew why he had come, and she wanted to determine whether he had the wisdom to bear the royal umbrella. So she gave a command that he should come.

On hearing the command and wanting to please her, he ran quickly up from the foot of the staircase and stood by her. Then to test him, she said, “Run quickly on the level ground.” He sprang forward, thinking that he was pleasing the princess. She said to him, “Come here.” He went up with all speed. She saw his lack of wisdom and said, “Come and rub my feet.” To please her, he sat down and rubbed her feet. Then she struck him on the breast with her foot and made him fall on his back. She signaled to her female attendants: “Beat this blind and senseless fool and seize him by the throat and throw him out.” This they did.

“Well, general?” they said to him. He replied, “Do not mention it. She is not a human being.” Then the treasurer went, but she put him to shame in the same way. So, too, it was with the cashier, the keeper of the umbrella, and the sword bearer. She put them all to shame.

Then the multitude deliberated and said, “No one can please the princess. Give her to him who can string the bow that requires the strength of a thousand men.” But no one could string it. Then they said, “Give her to him who knows which is the head of the square bed.” But no one knew it. “Then give her to him who is able to draw out the 16 great treasures.” But no one could draw them out.

Then they consulted together: “The kingdom cannot be preserved without a king. What is to be done?” Then the family priest said to them, “Do not be fear. We must send out the festive carriage. The king who is obtained by the festival carriage will be able to rule over all India.” So they agreed, and having decorated the city and yoked four lotus-colored horses to the festive chariot and spread a coverlet over them and fixing the five ensigns of royalty, they surrounded them with an army of four hosts.

Musical instruments are sounded in front of a chariot that contains a rider, but behind one that contains none. So the family priest, having told them to place the musical instruments behind the chariot, and having sprinkled the strap of the car and the goad with a golden jar, commanded the chariot to proceed to him who has merit sufficient to rule the kingdom.

The car went solemnly around the palace and proceeded up the kettledrum road. The general and the other officers of state each thought that the car was coming to him, but it passed by their houses. And having gone solemnly around the city, it went out by the eastern gate and passed on to the park. When they saw it going along so quickly, they thought to stop it. But the family priest said, “Do not stop it. Let it go a hundred leagues if it pleases.”

The car entered the park and went solemnly around the ceremonial stone. It stopped as if ready to be mounted. The family priest saw the Bodhisatta lying there. He addressed the ministers: “Sirs, I see someone lying on the stone. We do not know if he has the wisdom worthy of the white umbrella or not. If he is a being of holy merit, he will not look at us, but if he is a creature of ill omen, he will look up in alarm and look at us trembling. Sound forth all the musical instruments.”

Quickly they sounded the hundreds of instruments. It was like the noise of the sea. The Great Being awoke at the noise, and having uncovered his head and looked round, he saw the great multitude. He perceived that it must be the white umbrella that had come to him. He again wrapped his head and turned around and lay on his left side. The family priest uncovered his feet and—beholding the marks—said, “Not to mention one continent, he is able to rule all the four.” So he told them to sound the musical instruments again.

The Bodhisatta uncovered his face, and having turned around, he lay on his right side and looked at the crowd. The family priest comforted the people and folded his hands. He bent down and said, “Rise, my lord, the kingdom belongs to you.” “Where is the king?” he replied.

“He is dead.” “Has he left no son or brother?” “None, my lord.” “Well, I will take the kingdom.” So he rose and sat down cross-legged on the stone slab. Then they anointed him then and there. And he was called King Mahājanaka. He mounted the chariot, and having entered the city with royal magnificence, he went up to the palace and mounted the dais. He arranged the different positions for the general and the other officers.

Now the princess, wishing to test him by his first behavior, sent a man to him, saying, “Go to the king and tell him, ‘the princess Sīvalī summons you. go quickly to her’.” The wise king acted as if he did not hear his words. He went on with his description of the palace, “Thus and thus will it be well.” The messenger, being unable to attract his attention, left. He told the princess, “Lady, the king heard your words, but he only keeps on describing the palace and utterly disregards you.” She said to herself, “He must be a man of a lofty status.” She sent a second and even a third messenger.

The king at last ascended the palace. He walked at his own pleasure and at his usual pace, yawning like a lion. As he drew near, the princess could not stand still before his majestic bearing. She went up to him and gave him her hand to lean on. He caught hold of her hand and ascended the dais. And having seated himself on the royal couch beneath the white umbrella, he asked the ministers, “When the king died, did he leave any instructions with you?” Then they told him that the kingdom was to be given to him who could please the princess Sīvalī. “The princess Sīvalī gave me her hand to lean on as I came near. I have therefore succeeded in pleasing her. Tell me something else.”

“He said that the kingdom was to be given to him who could decide which was the head of the square bed.” The king replied, “This is hard to tell, but it can be known by a contrivance.” He took out a golden needle from his head and put it into the princess’ hand, saying, “Put this in its place.” She took it and put it in the head of the bed. Thus they also say in the proverb, “She gave him a sword.” By that indication he knew which was the head, and, as if he had not heard it before, he asked what they were saying. When they repeated it, he replied, “It is not a wonderful thing for one to know which is the head.”

Then he asked if there were any other test. “Sire, he commanded us to give the kingdom to him who could string the bow which required the strength of a thousand men.” When they had brought it at his order, he strung it while sitting on the bed as if it were only a woman’s bow for carding cotton. “Tell me something else,” he said.

“He commanded us to give the kingdom to him who could draw out the 16 great treasures.” “Is there a list?” he asked. They repeated the list. As he listened, the meaning became clear to him like the moon in the sky. “There is not time today, but we will take the treasure tomorrow.”

On the next day, he assembled the ministers. He asked them, “Did your king feed pacceka buddhas?” When they answered in the affirmative, he thought to himself, “The sun cannot be this sun, but pacceka buddhas are called suns from their likeness. The treasure must be where he used to go and meet them.” Then he asked them, “When the pacceka buddhas came, where did he meet them?” They told him of the place. He told them to dig that spot and draw out the treasure from there, which they did. “When he followed them as they departed, where did he stand as he bade them farewell?” They told him, and he had them draw out the treasure from there, which they also did.

The great multitude uttered thousands of shouts and expressed their joy and gladness of heart, saying, “When they heard before of the rising of the sun, they used to wander about, digging in the direction of the actual sunrise. And when they heard of his setting, they used to go digging in the direction of the actual sunset. But here are the real riches. Here is the true marvel.”

When they said, “The treasure within,” he drew out the treasure of the threshold within the great gate of the palace. “The treasure outside,”—he drew out the treasure of the threshold outside. “Neither within nor without,”—he drew out the treasure from below the threshold. “At the mounting,”—he drew out the treasure from the place where they planted the golden ladder for mounting the royal state elephant. “At the dismounting,”—he drew out the treasure from the place where they dismounted from the royal elephant’s shoulders. “The four great sāl-pillars,”—there were four great feet, made of sāl-wood, of the royal couch where the courtiers made their prostrations on the ground. And from under them, he brought out four jars full of treasure.

“A yojana round,”—now a yojana is the yoke of a chariot, so he dug a yoke around the royal couch and brought out jars of treasure from there. “The treasure at the end of the teeth,”—in the place where the royal elephant stood, he brought out two treasures from the spot in front of “his two tusks.” “At the end of his tail,”—at the place where the royal horse stood, he brought out jars from the place opposite his tail. “In the kebuka,”—now water is called kebuka; so he had the water of the royal lake drawn off and there revealed a treasure. “The treasure at the ends of the trees,”—he drew out the jars of treasure buried within the circle of shade thrown at midday under the great sāl trees in the royal garden.

In this way he brought out the 16 treasures. He asked if there was anything more, and they answered “No.” The multitude were delighted. The king said, “I will throw this wealth in the mouth of charity.” So he had five halls for alms erected in the middle of the city, and at the four gates, he made a great distribution. Then he sent for his mother and the brahmin from Kāḷacampā, and he paid them great honor.

In the early days of his reign, King Mahājanaka, the son of Ariṭṭhajanaka, ruled over all the kingdoms of Videha. “The king, they say, is wise. We will see him,” The whole city was excited to see him. They came from different places with presents. They prepared a great festival in the city. They covered the walls of the palace with plastered impressions of their hands. They hung perfumes and flower-wreaths. They darkened the air as they threw fried grain, flowers, perfumes and incense, and they got all sorts of food ready to eat and drink. To present offerings to the king, they gathered round and stood, bringing food hard and soft and all kinds of drinks and fruits.

While a crowd of the king’s ministers sat on one side, a host of brahmins sat on another side. There were wealthy merchants and the like, on there were the most beautiful dancing girls. There were brahmin laudators who were skilled in festive songs. They sang their cheerful odes with loud voices. They played hundreds of musical instruments. The king’s palace was filled with one vast sound as if it were in the center of the Yugandhara Ocean (one of the seas between the seven concentric circles of rock round Meru). Every place on which he looked trembled.

The Bodhisatta sat under the white umbrella and beheld the great pomp and glory like Sakka’s magnificence. And he remembered his own struggles in the great ocean. “Courage is the right thing to put forth. if I had not shown courage in the great ocean, I should never have attained this glory.” Joy arose in his mind as he remembered it, and he burst into a triumphant utterance. Afterwards he fulfilled the ten royal duties (generosity, morality, renunciation, honesty, gentleness, asceticism, non-violence, patience, uprightness). He ruled righteously and waited on the pacceka buddhas.

In the course of time, Queen Sīvalī brought forth a son endowed with all the auspicious marks. They called him Dīghāvu-kumāra. When he grew up, his father made him viceroy. One day, when various sorts of fruits and flowers were brought to the king by the gardener, he was pleased when he saw them. He showed him honor, and he told him to adorn the garden and then he would pay it a visit. The gardener carried out these instructions and told the king, and he, seated on a royal elephant and surrounded by his retinue, entered at the garden gate.

Now near it stood two bright green mango trees. One of them was without fruit, and the other one was full of very sweet fruit. As the king had not eaten the fruit, no one else ventured to gather any. And the king, as he rode on his elephant, picked a fruit and ate it. The moment the mango touched the end of his tongue, a divine flavor seemed to arise, and he thought to himself, “When I return, I will eat several more.” But once it was known that the king had eaten the fruit of the tree, everybody from the viceroy to the elephant keepers gathered and ate some. Those who did not take the fruit broke the boughs with sticks and stripped off the leaves until that tree stood all broken and battered. The other tree, however, stood as beautiful as a mountain of gems.

As the king came out of the garden, he saw it and asked his ministers about it. “The crowd saw that your majesty had eaten the first fruit, and they plundered it,” they replied. “But this other tree has not lost a leaf or any color.” “It has not lost them because it had no fruit.” The king was greatly moved. “This tree keeps its bright green because it has no fruit, while its fellow is broken and battered because of its fruit. This kingdom is like the fruitful tree, but the ascetic life is like the barren tree. One who possesses property has fears, not one who is without anything of his own. Far from being like the fruitful tree, I will be like the barren one. I will leave my glory behind. I will give up the world and become an ascetic.”

Having made this firm resolution, he entered the city. And standing at the door of the palace, he sent for his commander-in-chief. He said to him, “O general, from this day forth let no one see my face except one servant to bring me my food and another to give me water for my mouth and a toothbrush. You take my old chief judges, and with their help, govern the kingdom. From now on I will live the life of a priest on the top of the palace.” So saying, he went up to the top of the palace alone where he lived as a priest.

As time passed, the people assembled in the courtyard. And when they did not see the Bodhisatta they said, “He is not like our old king,” and they repeated two stanzas:

“Our king, the lord of all the earth, is changed from what he was of old,

He heeds no joyous song today nor cares the dancers to behold.

“The deer, the garden, and the swans fail to attract his absent eye,

Silent he sits as stricken dumb and lets the cares of state pass by.”

They asked the butler and the attendant, “Does the king ever talk to you?” “Never,” they replied. Then they related how the king, with his mind plunged in ideas and detached from all desires, had remembered his old friends the pacceka buddhas. He had said to himself, “Who will show me the dwelling place of those beings free from all attachments and possessed of all virtues?” He had uttered aloud his intense feelings in three stanzas:

“Hidden from sight, intent on bliss, freed from all bonds and mortal fears,

In whose fair garden, old and young, together dwell those heavenly seers?

They have left all desires behind, those happy glorious saints I bless,

Amidst a world by passion tossed they roam at peace and passionless.

They have all burst the net of death, and the deceiver’s outspread snare,

Freed from all ties, they roam at will, O who will guide me where they are?”

Four months passed as he led an ascetic’s life on the palace. At last his mind turned intently towards giving up the world. His own home seemed like one of the hells between the sets of worlds, and the three modes of existence (impermanence, non-self, and dukka) presented themselves to him as all on fire. In this frame of mind, he burst into a description of Mithilā as he thought, “When will the time come that I shall be able to leave this Mithilā, adorned and decked out like Sakka’s palace, and go to Himavat and there put on the ascetic’s dress?”

“When shall I leave this Mithilā, spacious and splendid though it be,

By architects with rule and line laid out in order fair to see.

With walls and gates and battlements, traversed by streets on every side,

With horses, cows, and chariots thronged, with tanks and gardens beautified,

Videha’s far-famed capital, gay with its knights and warrior swarms,

Clad in their robes of tiger skins, with banners spread and flashing arms,

Its brahmins dressed in Kāçi cloth, perfumed with sandal, decked with gems,

Its palaces and all their queens with robes of state and diadems!

(A “diadem” is a crowned head.)

When shall I leave them and go forth, the ascetic’s lonely bliss to win,

Carrying my rags and water pot, when will that happy life begin?

When shall I wander through the woods, eating their hospitable fruit,

Tuning my heart in solitude as one might tune a seven-stringed lute,

Cutting my spirit free from hope of present or of future gain,

As the cobbler when he shapes his shoe cuts off rough ends and leaves it plain.”

Now he had been born at a time when men lived to the age of 10,000 years. So after reigning for 7,000 years, he became an ascetic while 3,000 years remained of his life. And when he had embraced the ascetic life, he still lived in the palace four months after he saw the mango tree. But thinking to himself that an ascetic’s house would be better than the palace, he secretly instructed his attendant to have some yellow robes and an earthen vessel brought to him from the market. He then sent for a barber and had him cut his hair and beard. He put on one yellow robe as the under dress, another as the upper, and the third he wrapped over his shoulder. And having put his vessel in a bag, he hung it on his shoulder. Then, he took his walking stick and walked several times backwards and forwards on the top story with the triumphant step of a pacceka buddha.

That day he continued to live there, but on the next day at sunrise, he began to go down. Queen Sīvalī sent for 700 favorite concubines, and she said to them, “It has been a long time—four full months—since we last saw the king. But we will see him today. Do all you can to adorn yourselves and put forth your graces and blandishments and try to entangle him in the snares of passion.” Attended by them all arrayed and adorned, she ascended the palace to see the king. But although she met him coming down, she did not recognize him. She thought that it was a pacceka buddha who had come to instruct the king. She made a salutation and stood on one side while the Bodhisatta came down from the palace.

But after she had ascended the palace, the queen saw the king’s hair. It was the color of bees, and it was lying on the royal bed with the articles of his toilet. She exclaimed, “That was no pacceka buddha. It must have been our own dear lord. We will beg him to come back.” So she descended from the upper story and went to the palace yard. She and all the attendant queens unloosed their hair and let it fall on their backs. They beat their breasts with their hands following the king and wailing plaintively. “Why do you do this thing, O great king?” The whole city was disturbed, and all the people followed the king weeping. “Our king, they say, has become an ascetic. How shall we ever find such a just ruler again?”

Then the Master, as he described the women’s weeping and how the king left them all and went on, uttered these stanzas:

“There stood the seven hundred queens, stretching their arms in pleading woe,

Arrayed in all their ornaments, ‘Great king, why do you leave us so?’

“But leaving those seven hundred queens, fair, tender, gracious, the great king

Followed the guidance of his vow, with stern resolve unfaltering.

“Leaving the inaugurating cup, the old sign of royal pomp and state,

He takes his earthen pot today, a new career to inaugurate.”

(An inaugurating cup is a golden jar used at a king’s coronation.)

The weeping Sīvalī found herself unable to stop the king. She sent for the commander-in-chief and told him to start a fire before the king among the old houses and ruins which lay in the direction where he was going, and to heap up grass and leaves and create smoke in different places. He did so. Then she went to the king, and falling at his feet, she told him in two stanzas that Mithilā was in flames.

“Terrible are the raging fires, the stores and treasures burn,

The silver, gold, gems, shells, and pearls are all consumed in turn.

“Rich garments, ivory, copper, skins, all meet one ruthless fate.

Turn back, O king, and save your wealth before it is too late.”

The Bodhisatta replied, “What are you saying, O queen? the possessions of those who have things can be burned, but I have nothing:

“We who have nothing of our own may live without a care or sigh,

Mithilā’s palaces may burn, but naught of mine is burned thereby.”

So saying, he went out by the northern gate. His queens also went out. Queen Sīvalī told them to show him how the villages were being destroyed and the land wasted. They pointed out how armed men were running about and plundering in different directions, while others, covered with red lac, were being carried as wounded or dead on boards. The people shouted, “O king, while you guard the kingdom, they spoil and kill your subjects.” Then the queen repeated a stanza, imploring the king to return:

“Wild foresters lay waste the land, return, and save us all,

Let not your kingdom, left by you, in hopeless ruin fall.”

The king reflected, “No robbers can rise up to spoil the kingdom while I am ruling. This must be Sīvalīdevī’s invention.” So he repeated these stanzas to show that he did not understand her:

“We who have nothing of our own may live without a care or sigh,

The kingdom may lie desolate, but naught of mine is harmed thereby.

“We who have nothing of our own may live without a care or sigh,

Feasting on joy in perfect bliss like an Ābhassara deity.”

(Ābhassara is a class of radiant devas inhabiting a heaven in the Rūpaloka form realm and specifically within the second jhāna.)

Even after he said this the people still followed. Then he said to himself, “They do not wish to return. I will make them go back.” So after he had gone about half a mile, he turned back. He stood in the high road and asked his ministers, “Whose kingdom is this?” “Yours, O king.” “Then punish whosoever passes over this line.” Then he drew a line with his staff. No one was able to violate that line, and the people, standing behind that line, made loud lamentations.

The queen was also unable to cross that line. And beholding the king going on with his back turned towards her, she could not restrain her grief. She beat her breast, and—falling across—forced her way over the line. The people cried, “The line guardians have broken the line,” and they followed where the queen led.

The Great Being went towards the Northern Himavat (Himalaya Mountains). The queen also went with him, taking along the army and the animals for riding. Unable to stop the multitude, the king traveled on for sixty leagues.

Now at that time an ascetic named Nārada lived in the Golden Cave in Himavat. (The Golden Cave is where the pacceka buddhas lived.) He possessed the five supernatural faculties (faith, energy, mindfulness, concentration, and wisdom). After passing seven days in meditative rapture, he ended his trance and shouted triumphantly, “O the bliss, O the bliss!” (This is reminiscent of the Bhaddiya Sutta, Ud 2.10.) He used his divine eye to see if there was anyone in India who was seeking this bliss. He saw Mahājanaka, the potential Buddha. He thought, “The king has made the great renunciation, but he cannot turn the people back who follow him headed by Queen Sīvalī. They may be a hindrance to him. I will exhort him to encourage his purpose.” So using his divine power, he stood in the air in front of the king and spoke to strengthen his resolve:

“Wherefore is all this noise and din, as of a village holiday?

Why is this crowd assembled here? Will the ascetic kindly say?”

The king replied:

“I’ve crossed the bound and left the world, ‘tis this has brought these hosts of men,

I leave them with a joyous heart: you know it all, why ask me then?”

Then the ascetic repeated a stanza to confirm his resolve:

“Think not that you already crossed, while with this body still beset,

There are still many foes in front, you have not won your victory yet.”

The Great Being exclaimed:

“No pleasures known or those unknown have power my steadfast soul to bend,

What foe can stay me in my course as I press onwards to the end?”

Then he repeated a stanza, declaring the hindrances:

“Sleep, sloth, loose thoughts to pleasure turned, desire, a discontented mind,

The body brings these bosom guests, many a hindrance you will find.”

The Great Being then praised him in this stanza:

“Wise, brahmin, are your warning words, I thank you, stranger, for the same,

Answer my question if you will, who are you, say, and say your name.”

Nārada replied:

“Know I am Nārada by name, a Kassapa, my heavenly rest

I have just left to tell you this, to associate with the wise is best.

The four perfections exercise, find in this path your highest joy,

Whate’er it be you lack it yet, by patience and by calm supply.

High thoughts of self, low thoughts of self, nor this, nor that befits the sage,

Be virtue, knowledge, and the law the guardians of your pilgrimage.”

Nārada then returned through the sky to his own abode. After he had gone, another ascetic, named Migājina, who had just arisen from meditative rapture, saw the Great Being. He, too, resolved to utter an exhortation to him that he might send the multitude away. So he appeared above him in the air and spoke:

“Horses and elephants, and they who in city or in country dwell,

You have left them all, O Janaka, an earthen bowl contents you well.

“Say, have your subjects or your friends, your ministers or kinsmen dear,

Wounded your heart by treachery that you have chosen this refuge here?”

The Bodhisatta replied:

“Never, O seer, at any time, in any place, on any plea,

Have I done wrong to any friend or any friend done wrong to me.

“I saw the world devoured by pain, darkened with misery and chagrin,

I watched its victims bound and slain, caught helplessly its toils within,

I drew the warning to myself and here the ascetic’s life begin.”

The ascetic, wishing to hear more, asked him:

“None choose the ascetic’s life unless some teacher points the way,

By practice or by theory, who was your holy teacher, say.”

The Great Being replied:

“Never at any time, O seer, have I heard words that touched my heart

From brahmin or ascetic lips, bidding me choose the ascetic’s part.”

He then told him why he had left the world:

“I wandered through my royal park one summer’s day in all my pride,

With songs and tuneful instruments filling the air on every side.

“And there I saw a mango tree, which near the wall had taken root,

It stood all broken and despoiled by the rude crowds that sought its fruit.

“Startled I left my royal pomp and stopped to gaze with curious eye,

Contrasting with this fruitful tree a barren one which grew close by.

“The fruitful tree stood there forlorn, its leaves all stripped, its branches bare,

The barren tree stood green and strong, its foliage waving in the air.

We kings are like that fruitful tree, with many a foe to lay us low,

And rob us of the pleasant fruit which for a little while we show.

“The elephant for ivory, the panther for his skin is slain,

Houseless and friendless at the last the wealthy find their wealth their bane,

That pair of trees my teachers were, from them my lesson did I gain.”

Migājina, having heard the king, exhorted him to be earnest and returned to his own home.

When he had gone, Queen Sīvalī fell at the king’s feet, and said

“In chariots or on elephants, footmen or horsemen, all as one,

Your subjects raise a common wail, ‘Our king has left us and is gone!’

“O comfort first their stricken hearts and crown your son to rule instead,

Then, if you will, forsake the world the pilgrim’s lonely path to tread.”

The Bodhisatta replied:

“I’ve left behind my subjects all, friends, kinsmen, home and native land,

But the nobles of Videha race, Dīghāvu trained to bear command,

Fear not, O queen of Mithilā, they will be near to uphold your hand.”

(Dīghāvu was his son.)

Figure: “What am I to do?”

The queen exclaimed, “O king, you have become an ascetic. What am I to do?” Then he said to her, “I will counsel you. Carry out my words.” He addressed her in this way:

“If you would teach my son to rule, wicked in thought, and word, and deed,

An evil ending will be yours, this is the destiny decreed.

A beggar’s portion, gained as alms, so say the wise, is all we need.”

In this way he counselled her. And while they went on, talking together, the sun set.

The queen camped in a suitable place, while the king went to the root of a tree and passed the night there. On the next day, after washing, he went on his way. The queen gave orders that the army should follow him. At the time for alms rounds, they reached a city called Thūṇā.

At that time there was a man in the city who had bought a large piece of flesh at a slaughterhouse. He fried it on a prong with some coals and placed it on a board to cool. But while he was distracted, a dog ran off with it. The man pursued it as far as the southern gate of the city. But he was too tired to continue, and he stopped there.

The king and queen came up separately in front of the dog. The dog was startled when he saw them, so he dropped the meat and ran off. The Great Being saw this and reflected, “He has dropped it and run off. The real owner is unknown. There is not another piece of alms as good as this. I will eat it.” So he took out his own earthen dish, seized the meat, and he wiped it off. He put it on the dish, went to a pleasant spot where there was some water, and there he ate it.

The queen thought to herself, “If the king were worthy of the kingdom, he would not eat the dusty leavings of a dog. He is not really my husband.” She said aloud, “O great king, do you eat such a disgusting morsel?” “It is your own blind folly,” he replied, “that prevents you from seeing the special value of this piece of alms.” So he carefully examined the spot where it had been dropped and ate it as if it were ambrosia. Then he washed his mouth and his hands and feet.

Then the queen addressed him in words of blame:

“Should the fourth eating time come round, a man will die if still he fast,

Yet for all that the noble soul would loathe so foul a mess to taste.

“This is not right that you have done, shame on you, shame, I say, O king,

Eating the leavings of a dog, you have done a most unworthy thing.”

The Great Being replied:

“Leavings of householder or dog are not forbidden food, I glean,

If it be gained by lawful means, all food is pure and lawful, queen.”

As they talked together, they reached the city-gate. Some boys were playing there, and a girl was shaking some sand in a small winnowing (grain) basket. There was a single bracelet on one of her hands, and on the other hand there were two bracelets. These two jangled together, and the other one was noiseless. The king saw the incident and thought to himself, “Sīvalī keeps following me. A wife is an ascetic’s bane. Men will blame me and say that even when I have left the world, I cannot leave my wife. If this girl is wise, she will be able to tell Sīvalī the reason why she should turn back and leave me. I will hear her story and send Sīvalī away.” So he said to her:

“Nestling beneath your mother’s care, girl, with those trinkets on you bound,

Why is one arm so musical while the other never makes a sound?”

The girl replied:

“Ascetic, on this hand I wear two bracelets fast instead of one,

‘Tis from their contact that they sound, ’tis by the second this is done.

“But mark this other hand of mine, a single bracelet it does wear,

That keeps its place and makes no sound, silent because no other’s there.

The second jangles and makes jars, that which is single cannot jar,

Would you be happy? Be alone. Only the lonely happy are.”

Having heard the girl’s words, he took up the idea and addressed the queen:

“Hear what she says. This servant girl would overwhelm my head with shame

Were I to yield to your request. It is the second brings the blame.

“Here are two paths. You take that one, the other by myself take I.

Call me not husband from henceforth, you are no more my wife. Goodbye.”

When she heard him, the queen told him to take the better path to the right while she chose the left. But after going a little way, she was unable to restrain her grief. She went back to him again, and she and the king entered the city together.

Explaining this, the Master said: “With these words on their lips, they entered the city of Thūṇā.”

After they had entered the city, the Bodhisatta went on his alms round. He reached the door of the house of a maker of arrows, while Sīvalī stood on one side.

Now at that time the arrow-maker had heated an arrow in a pan of coals and had wetted it with some sour rice gruel. He closed one eye, while looking with the other to make sure that the arrow was straight. The Bodhisatta reflected, “If this man is wise, he will be able to explain the incident. I will ask him.” So he went up to him.

The Master described what happened in a stanza:

“To a fletcher’s house he came for alms, the man with one eye closed did stand,

And with the other sideways looked to shape the arrow in his hand.”

Then the Great Being said to him:

“One eye you close and you do gaze with the other sideways, is this right?

I pray, explain your attitude, do you think it improves your sight?”

He replied:

“The wide horizon of both eyes serves only to distract the view,

But if you get a single line, your aim is fixed, your vision true.

“It is the second that makes jars, that which is single cannot jar,

Would you be happy? Be alone. Only the lonely happy are.”

After these words of advice, he was silent. The Great Being proceeded on his round. And having collected some food of various sorts, he left the city. He sat down in a spot pleasant with water. And having done all he had to do, he put away his bowl in his bag and addressed Sīvalī:

“You heard now the fletcher, like the girl, he would o’erwhelm my head with shame

Were I to yield to your request. It is the second brings the blame.

“Here are two paths: you take that one, the other by myself take I,

Call me not husband from henceforth, you are no more my wife. Goodbye.”

Nonetheless, she continued to follow him even after this speech. But she could not persuade the king to turn back, and the people followed her.

Now there was a forest not far off, and the Great Being saw a dark tract of trees. He wanted to make the queen turn back. He saw some muñja grass near the road. So he cut off a stalk of it and said to her, “See, Sīvalī, this stalk cannot be joined again. So our relationship can never be joined again.” And he repeated this half stanza:

“Like to a muñja reed full-grown, live on, O Sīvalī, alone.”

When she heard him, she said, “I will no longer have a relationship with King Mahājanaka.” And being unable to control her grief, she beat her breast with both hands and fell senseless on the road.

The Bodhisatta saw that she was unconscious. He plunged into the wood, carefully covering up his footsteps. His ministers went and sprinkled her body with water. They rubbed her hands and feet, and at last she recovered consciousness. She asked, “Where is the king?” “Do you not know?” they said. “Search for him,” she cried. But even though they ran here and there they could not find him. So she made a great lamentation, and after erecting a stupa where he had stood, she offered worship with flowers and perfumes. Then she returned.

The Bodhisatta entered the region of Himavat, and in the course of seven days he perfected the Faculties (1) faith/confidence, 2) energy, 3) mindfulness, 4) concentration/samadhi and 5) wisdom/insight) and the Attainments (jhānas). He never returned to the land of men.

The queen also erected stupas on the spots where he had talked to the arrow-maker and with the girl, where he had eaten the meat, and where he had talked to Migājina and with Nārada. She made offerings of flowers and perfumes. And then, surrounded by the army, she entered Mithilā. She had her son’s coronation performed in the mango garden. She had him enter the city with the army. But she herself, having adopted the ascetic life, lived in that garden. She practiced the preparatory practices for developing mystic meditation (jhāna) until at last she attained meditative absorption and became destined to rebirth in the Brahma world.

End of story in the present...